armies in plastic today look at all the 4 posts before this

Menabrea's administration was then upon the eve of falling. The cause was one of those financial crises that were symptomatic of a mischief which has been growing from then till now, when some critics think they see in it the fatal upas tree of Italy.

new war museum planned for gravelotte

new war museum planned for gravelotteThe process of transforming a country where everything was wanting—roads, railways, lines of navigation, schools, water, lighting, sanitary provisions, and the other hundred thousand requirements of modern life—into the Italy of to-day, where all these things have made leaps almost incredible to those who knew her in her former state, has proved costly without example.

flat

flat It may be said that if the path entered upon by the man who took charge of the exchequer after Menabrea's fall, Quintino Sella, had been rigorously followed by his successors, the after situation would not be what it later became.

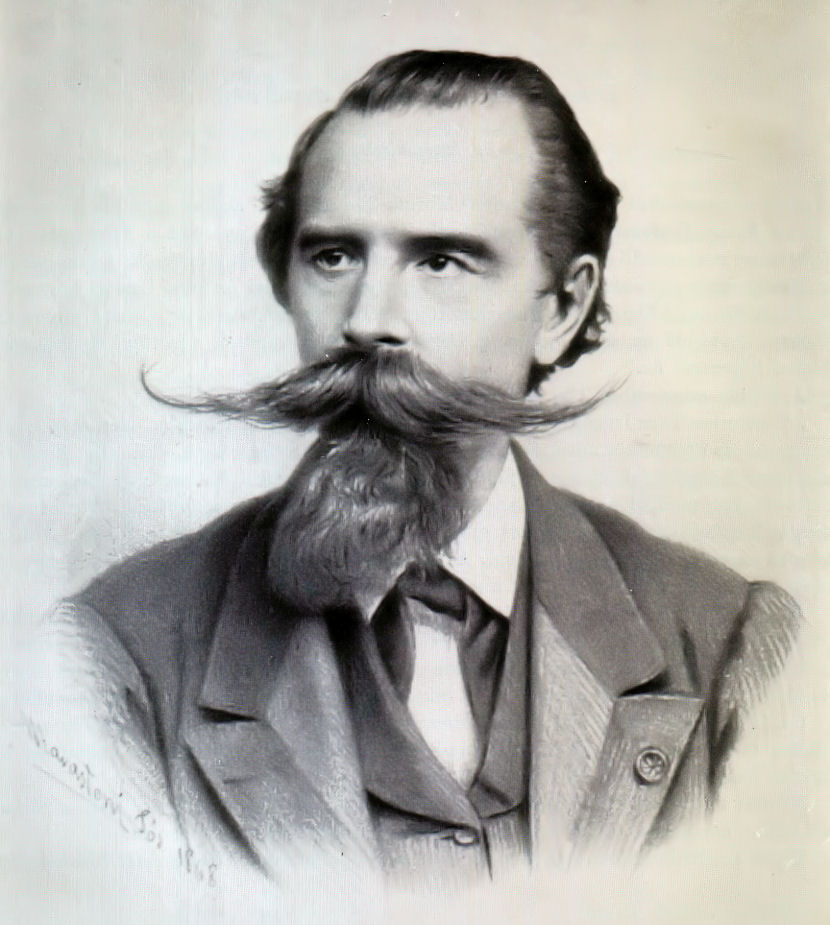

Giovanni Lanza assumed the premiership in the government in which Sella was Minister of Finance. Both these politicians were Piedmontese, and both were known as men of conspicuous integrity, but Lanza's rigid conservatism made it seem unlikely that the Roman question would take a fresh turn under his administration. In politics, however, the unlikely is what generally happens; events are stronger than men.

lanza

lanzaOn the 8th of December the twenty-first Ecumenical Council assembled in Rome. From the day of its meeting, in spite of the strenuous opposition of its most learned and illustrious members, there was no more doubt that the dogma under consideration would be voted by the partly astute and partly complaisant majority than that it would have been rejected in the twenty preceding Councils. On the 18th of July 1870, the Pope was proclaimed Infallible.

BATTLE OF WORTH above

That was a moment of excitement such as has not often thrilled Europe, but the cause was not the Infallibility of Pius IX. On the 16th, Napoleon declared war with Prussia. War, like death, comes as a shock, however plainly it has been foreseen; besides, it was only the well-informed who knew how near the match had been to the powder-magazine for two years and more.

Whether the explosion, at the last, was timed by Napoleon or by Bismarck is not of great importance; it could have been but little delayed.

Napoleon was beset alike by the revolutionary spectre and by the gaunt King of Terrors; he knew the throw was desperate, but with the gambler's instinct, which had always been so strong in him, he was magnetised by it because it was desperate.

Pitiful egotist though he was, history may forgive him sooner than it forgives the selfish Chauvinism of Thiers, who had been goading his countrymen to war ever since Sadowa, or the insane bigotry of the party which, having triumphed over revolution at Mentana, now sought to triumph over heresy in what the Empress called 'Ma guerre.'

Napoleon had the remaining sagacity to see the extreme danger of leaving a few thousand men isolated in Rome at a time when, happen what might, it would be impossible to reinforce them.

Directly after declaring war, notwithstanding the cries of the Ultramontanes, he decided on recalling the French troops.

He induced the Italian Government to resume the obligations of the September Convention, by which the inviolability of the Papal frontier was guaranteed. Lanza is open to grave criticism for entering into a contract which it was morally certain that he would not be able to keep.

Perhaps he hoped that Napoleon would himself release Italy from her bond. But the 'Jamais' of Rouher stood in the way. Could the Emperor, after such boasting, coolly throw the Pope overboard the first time it suited his convenience? Moreover, his present Prime Minister, M. Emile Olivier, when the question was put to him, did not hesitate to renew the declaration that the Italians must not be allowed to go to Rome.

Napoleon made some last frantic efforts to get Austria and Italy to befriend him unconditionally. How far he knew the real state of his army before he declared war may be doubtful, but that he possessed overwhelming proof of it, even before the first defeats, cannot be doubted at all. His heart was not so light as his Prime Minister's.

At the end of July he sent General Türr on a secret mission to try and obtain the help of Austria and Italy. The Hungarian general wrote from Florence, that unless something could be done to assure Italy that the national question would be settled in accordance with the wishes of her people, the Italian alliance was not possible. The Convention, he pointed out, was a bane instead of a boon to Italy.

This letter was answered by a telegram through the French Ambassador at Vienna: 'Can't do anything for Rome; if Italy will not march, let her stand still.

turr

turrAs in the former negotiations, Austria took her stand on precisely the same ground as Italy. And thus it was that France plunged into the campaign of 1870 single-handed.

gra velotte today

gra velotte todayAfter Wörth(below), and once more after Gravelotte, the endeavour to draw Italy into the struggle was renewed. Napoleon was aware that Victor Emmanuel was wildly anxious to come to the rescue, and on this personal goodwill his last hope was built.

Prince Napoleon was despatched from the camp at Châlons to see what he could do. At this eleventh hour (19th August) Napoleon was ready to yield about Rome. At the camp, the influence which guided him in Paris was less felt, or it is probable that he would not have yielded even now. Prince Napoleon carried a sheet of white paper with the Emperor's signature at the foot. He showed it to Lanza when he reached Florence, and told him to fill it up as he chose. Whatever he asked for was already granted. A month before, such terms would have won both Italy and Austria—not now.

Prince Napoleon was despatched from the camp at Châlons to see what he could do. At this eleventh hour (19th August) Napoleon was ready to yield about Rome. At the camp, the influence which guided him in Paris was less felt, or it is probable that he would not have yielded even now. Prince Napoleon carried a sheet of white paper with the Emperor's signature at the foot. He showed it to Lanza when he reached Florence, and told him to fill it up as he chose. Whatever he asked for was already granted. A month before, such terms would have won both Italy and Austria—not now.

No comments:

Post a Comment