Things had been going, without much variation, from bad to worse in the Roman states, ever since 1815. Pius VII. (Chiaramonti), who died in 1823, was succeeded by Leo XII. (Genga), an old man who was in such enfeebled health that his death was expected at the time of his election, but, like a more famous pontiff, he made a sudden recovery, which was attributed to the act of a prelate, who, in prayer, offered his own life for the Pope's, and who died a few days after resolving on the sacrifice.

an old man who was in such enfeebled health that his death was expected at the time of his election, but, like a more famous pontiff, he made a sudden recovery, which was attributed to the act of a prelate, who, in prayer, offered his own life for the Pope's, and who died a few days after resolving on the sacrifice.

During this Pope's reign, the smallpox was rife in Rome, in consequence of the suppression of public vaccination. The next conclave, held in 1829, resulted in the election of Pius VIII. (Castiglioni da Cingoli), who died on the 30th of November 1830, and was followed by Gregory XVI. (Cappellari). In each conclave,

who died on the 30th of November 1830, and was followed by Gregory XVI. (Cappellari). In each conclave,  Austria had secured the choice of a 'Zealot,' as the party afterwards called Ultramontane.

Austria had secured the choice of a 'Zealot,' as the party afterwards called Ultramontane.

The last traces of reforms introduced by the French disappeared; criminal justice was again administered in secret; the police were arbitrary and irresponsible.

All over the Roman states, but especially in Romagna, the secret society of the Sanfedesti flourished exceedingly; whether, as is probable, an offshoot of the Calderai or of indigenous growth, its aims were the same.

(Sanfedesti were components of a popular movement anti-Republican fascism, the Sanfedisti in 1799 involved peasant masses and were the main exponents of banditry against the Neapolitan Republic; the movement was organized around the cardinal Fabrizio Dionigi Ruffo as Army of the Holy Faith in our Lord Jesus Christ)

The 1st Battalion of Infantry of the line of 1814-1863 of the Duchy of Modena was reconstituted from a group of enthusiasts of local history of St. Possidonio (MO). Dr. Alberto Menziani says . "The flag is the faithful reproduction of that donated to the battalion in 1820 by the Duchess Maria Beatrice and commands and orders are drawn from the "Regulation of the exercise and Manoeuvres for the troops on foot of s.a.r. Francesco IV" the Ducal Army Estense of 1816."

The 1st Battalion of Infantry of the line of 1814-1863 of the Duchy of Modena was reconstituted from a group of enthusiasts of local history of St. Possidonio (MO). Dr. Alberto Menziani says . "The flag is the faithful reproduction of that donated to the battalion in 1820 by the Duchess Maria Beatrice and commands and orders are drawn from the "Regulation of the exercise and Manoeuvres for the troops on foot of s.a.r. Francesco IV" the Ducal Army Estense of 1816."

The rising at Parma requires but little comment. The Empress Marie-Louise above neither hated her subjects, nor was hated by them, but her engagements with Austria prevented her from granting the demanded concessions, and she abandoned her state, to return to it, indeed, under Austrian protection, but without the odious corollary of vindictive measures which was generally meant by a restoration.

Much more important is the history of the Modenese revolution.

Apologists have been found for the Bourbons of Naples, but, if anyone ever said a good word for Francesco d'Este, it has escaped the notice of the present writer.

it has escaped the notice of the present writer.

Under a despotism without laws (for the edicts of the Prince daily overrode the Este statute book which was supposed to be in force),

Modena was far more in the power of the priests, or rather of the Jesuits, than any portion of the states of the Church. Squint-eyed, crooked in mind and bloodthirsty, Francis was as ideal a bogey-tyrant as can be discovered outside fiction.

In 1822, he hung the priest Giuseppe Andreoli on the charge of Carbonarism; and his theory of justice is amusingly illustrated by the story of his sending in a bill to Sir Anthony Panizzi—who had escaped to England—for the expenses of hanging him in effigy.

Francis felt deeply annoyed by the narrow limits of his dominions, and his annoyance did not decrease with the decreasing chances of his ousting the Prince of Carignano from the Sardinian throne. He was intensely ambitious, and one of his subjects, a man, in other respects, of high intelligence, thought that his ambition could be turned to account for Italy. It was the mistake over again that Machiavelli had made with Cesare Borgia.

Ciro Menotti, who conceived the plan of uniting Italy under the Duke of Modena, was a Modenese landed proprietor who had exerted himself to promote the industry of straw-plaiting, and the other branches of commerce likely to be of advantage to an agricultural population.

He was known as a sound philanthropist, an excellent husband and father, a model member of society. Francis professed to take an interest in industrial matters; Menotti, therefore, easily gained access to his person.

In all the negotiations that followed, the Modenese patriot was supported and encouraged by a certain Dr Misley, who was of English extraction, with whom the Duke seems to have been on familiar terms.

It appears not doubtful that Menotti was led to believe that his political views were regarded with favour, and that he also received the royal promise that, whatever happened, his life would be safe.

This promise was given because he had the opportunity of saving the Duke from some great peril—probably from assassination, though the particulars were never divulged.

Misley went to Paris to concert with the Italian committee which had its seat there; the movement in Modena was fixed for the first days of February. But spies got information of the preparations, and on the evening of the 3rd, before anything had been done, Menotti's house was surrounded by troops, and after defending it, with the help of his friends, for two hours, he was wounded and captured. Next day the Duke despatched the following note to the Governor of Reggio-Emilia: 'A terrible conspiracy against me has broken out. The conspirators are in my hands. Send me the hangman.—Francis.'

Not all, however, of the conspirators were in his hands; the movement matured, in spite of the seizure of Menotti, and Francis, 'the first captain in the world,' as he made his troops call him, was so overcome with fright that on the 5th of February he left Modena with his family, under a strong military escort, dragging after him Giro Menotti, who, when Mantua was reached, was consigned to an Austrian fortress.

Meanwhile, the revolution triumphed. Modena chose one of her citizens as dictator, Biagio Nardi, who issued a proclamation in which the words 'Italy is one; the Italian nation is one sole nation,' testified that the great lesson which Menotti had sought to teach had not fallen on unfruitful ground. Wild as were the methods by which, for a moment, he sought to gain his end, his insistance on unity nevertheless gives Menotti the right to be considered the true precursor of Mazzini in the Italian Revolution.

Now that the testing-time was come, France threw to the winds the principle announced in her name with such solemn emphasis. 'Precious French blood should never be shed except on behalf of French interests,' said Casimir Périer, the new President of the Council.

A month after the flight of the Duke of Modena, the inevitable Austrians marched into his state to win it back for him. The hastily-organised little army of the new government was commanded by General Zucchi, an old general of Napoleon, who, when Lombardy passed to Austria, had entered the Austrian service.

He now offered his sword to the Dictator of Modena, who accepted it, but there was little to be done save to retire with honour before the 6000 Austrians. Zucchi capitulated at Ancona to Cardinal Benvenuti, the Papal delegate.

Those of the volunteers who desired it were furnished with regular passports, and authorised to take ship for any foreign port.

The most compromised availed themselves of this arrangement, but the vessel which was to bear Zucchi and 103 others to Marseilles, was captured by the Austrian Admiral Bandiera, by whom its passengers were kidnapped and thrown into Venetian prisons, where they were kept till the end of May 1832.

This act of piracy was chiefly performed with a view to getting possession of General Zucchi, who was tried as a deserter, and condemned to twenty years' imprisonment.

Among the prisoners was the young wife of Captain Silvestro Castiglioni of Modena. 'Go, do your duty as a citizen,' she had said, when her husband left her to join the insurrection. 'Do not betray it for me, as perhaps it would make me love you less.' She shared his imprisonment, but just at the moment of the release, she died from the hardships endured.

By the end of the month of March, the Austrians had restored Romagna to the Pope, and Modena to Francis IV. In Romagna the amnesty published by Cardinal Benvenuti was revoked, but there were no executions; this was not the case in Modena. The Duke brought back Ciro Menotti attached to his triumphal car, and when he felt that all danger was past, and that the presence of the Austrians was a guarantee against a popular expression of anger, he had him hung.

'When my children are grown up, let them know how well I loved my country,' Menotti wrote to his wife on the morning of his execution. The letter was intercepted, and only delivered to his family in 1848.

The revolutionists found it in the archives of Modena. On the scaffold he recalled how he was once the means of saving the Duke's life, and added that he pardoned his murderer, and prayed that his blood might not fall upon his head.

No sooner had the Austrians retired from the Legations in July 1831, than the revolution broke out again. Many things had been promised, nothing performed; disaffection was universal, anarchy became chronic, and was increased by the indiscipline of the Papal troops that were sent to put it down.

The Austrians returned and the French occupied Ancona, much to the Pope's displeasure, and not one whit to the advantage of the Liberals. This dual foreign occupation of the Papal states lasted till the winter of 1838.On 27 April 1831, Charles Albert came to the throne he had so nearly lost. His reconciliation with his uncle, Charles Felix, had been effected after long and melancholy preliminaries.

To wash off the Liberal sins of his youth, or possibly with a vague hope of finding an escape from his false position in a soldier's death, he joined the Duc d'Angoulême's expedition against the Spanish Constitutionalists.

Carlos Maria Isidro, Infante of Spain, the leader of the Carlist cause and pretender to the Spanish throne.he Spanish Civil War of 1820–1823, also known as the Trienio Liberal, was fought in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. It was a conflict between royalists and liberals with Bourbon France intervening on the side of the royalists. The revolutionaries of 1820 succeeded in forcing the monarchs of Spain and the southern Italian kingdom of the Two Siciles to grant liberal constitutions against their wills. It also involved a French invasion of Spain in April 1823, aimed at restoring King Ferdinand VII to the Spanish throne. This invasion is known in France as the "Spanish Expedition" (expédition d’Espagne), and in Spain as "The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis".

Carlos Maria Isidro, Infante of Spain, the leader of the Carlist cause and pretender to the Spanish throne.he Spanish Civil War of 1820–1823, also known as the Trienio Liberal, was fought in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. It was a conflict between royalists and liberals with Bourbon France intervening on the side of the royalists. The revolutionaries of 1820 succeeded in forcing the monarchs of Spain and the southern Italian kingdom of the Two Siciles to grant liberal constitutions against their wills. It also involved a French invasion of Spain in April 1823, aimed at restoring King Ferdinand VII to the Spanish throne. This invasion is known in France as the "Spanish Expedition" (expédition d’Espagne), and in Spain as "The Hundred Thousand Sons of St. Louis".

His extraordinary daring in the assault of the Trocadero caused him to be the hero of the hour when he returned with the army to Paris; but the King of Sardinia still refused to receive him with favour—a sufficiently icy favour when it was granted—until he signed an engagement, which remained secret, to preserve intact during his reign the laws and principles of government which he found in force at his accession.

If there had been an Order of the Millstone, Charles Felix would doubtless have conferred it upon his dutiful nephew; failing that, he presented to him for signature this wonderful document, the invention of which he owed to Prince Metternich.

At the Congress of Verona in 1822, Charles Albert's claims to the succession were recognised, thanks chiefly to the Duke of Wellington, who represented England in place of Lord Londonderry (Castlereagh), that statesman having committed suicide just as he was starting for Verona.

Prince Metternich then proposed that the Prince of Carignano should be called upon to enter into an agreement identical with the compact he was brought to sign a couple of years later. In communicating the proposal to Canning, the Duke of Wellington wrote that he had demonstrated to Prince Metternich 'the fatality of such an arrangement,' but that he did not think that he had made the slightest impression on him. So the event proved; baffled for the moment, the Prince managed to put his plan in execution through a surer channel.

With the accession of Charles Albert appears upon the political scene a great actor in the Liberation of Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini.

Young and unknown, except for a vague reputation for restlessness and for talent which caused the government of Charles Felix to imprison him for six or seven months at Savona, Mazzini proposed to the new King the terms on which he might keep his throne, as calmly as Metternich had proposed to him the terms on which he might ascend it. The contrast is striking; on the one side the statesman, who still commanded the armed force of three-fourths of Europe, doing battle for the holy alliance of autocrats, for the international law of repression, for all the traditions of the old diplomacy; on the other, the young student with little money and few friends, already an exile, having no allies but his brain and his pen, who set himself, certain of success, to dissolve that mighty array of power and pomp.

All his life Charles Albert was a Faust for the possession of whose soul two irreconcilable forces contended; the struggle was never more dramatically represented than at this moment in the person of these two champions.

Mazzini's letter to Charles Albert, which was read by the King, and widely, though secretly, circulated in Piedmont, began by telling him that his fellow-countrymen were ready to believe his line of conduct in 1821 to have been forced on him by circumstances, and that there was not a heart in Italy that did not quicken at his accession, nor an eye in Europe that was not turned to watch his first steps in the career that now unfolded before him.

Mazzini in 1831 was twenty-six years of age. His father was a Genoese physician, his mother a native of Chiavari. She was a superior woman, and devoted more than a mother's care to the excitable and delicate child, who seemed to her (mothers have sometimes the gift of prophecy) to be meant for an uncommon lot. One of the few personal reminiscences that Mazzini left recorded, relates to the time and manner in which the idea first came to him of the possibility of Italians doing something for their country.

He was walking with his mother in the Strada Nuova at Genoa one Sunday in April 1821, when a tall, black-bearded man with a fiery glance held towards them a white handkerchief, saying: 'For the refugees of Italy.' Mazzini's mother, gave him some money, and he passed on. In the streets were many unfamiliar faces; the fugitives from Turin and Alessandria were gathered at Genoa before they departed by sea into exile. The impression which that scene made on the mind of the boy of sixteen was never effaced.

He did not succeed in making the majority of his countrymen republicans, but he contributed more than any other man towards inspiring the whole country with the desire for unity. Herein lies his great work. Without Mazzini, when would the Italians have got beyond the fallacies of federal republics, leagues of princes, provincial autonomy, insular home-rule, and all the other dreams of independence

In 1831, most educated Italians did not even wish for unity, the peasants could not have cared a less so who cared? Very few.

'Great revolutions,' he says again, 'are the work of principles rather than of bayonets.' It was by the diffusion of ideas that 'Young Italy' became a commanding factor in the events of the next thirty years. The insurrectional attempts planned under its guidance did not succeed, nor was it likely that they should succeed. Devised by exiles, at a distance, they lacked the first elements of success.

After these events, Mazzini could no longer carry on his propaganda in France. He took refuge in England, where a great part of his life was to be passed, and of which he spoke, to the last, as his second country. The first period of his residence in England was darkened by the deep distress and discouragement into which the recent events had plunged him; but his faith in the future prevailed, and he went on with his work.

london 1848

Another work that occupied him and consoled him was the rescue and moral improvement of the children employed by organ-grinders, and to call attention to the plight of these poor children

.

The Great Powers had presented to the Court of Rome in 1831 a memorandum, in which various moderate reforms and improvements were proposed as urgently necessary to put an end to the intolerable abuses which were rife in the states of the Church, and, most of all, in Romagna.

The abolition of the tribunal of the Holy Office, the institution of a Council of State, lay education, and the secularisation of the administration were among the measures recommended. In 1845 a certain Pietro Renzi collected a body of spirited young men at San Marino, and made a dash on Rimini, where he disarmed the small garrison.

The other towns were not prepared, and Renzi and his companions were obliged to retire into Tuscany; but the revolution, partial as it had been, raised discussion in consequence of the manifesto issued by its promoters, in which a demand was made for the identical reforms vainly advocated by European diplomacy on him by his sons, his treasure, and his army would all be spent for the Italian cause.'

The fifteen years' pontificate of Gregory XVI. ended on the 1st June of 1846. In spite of the care taken by those around him to keep the aged pontiff in a fool's paradise with regard to the real state of his dominions, a copy of The Late Events in Romagna fell into his hands, and considerably disturbed his peace of mind.

He sent two prelates to look into the condition of the congested provinces, and their tour, though it resulted in nothing else, called forth new protests and supplications from the inhabitants, of which the most noteworthy was an address written by Count Aurelio Saffi, who was destined to pass many honourable years of exile in England.

This address attacked the root of the evil in a passage which exposed the unbearable vexations of a government based on espionage.

The acknowledged power of an irresponsible police was backed by the secret force of an army of private spies and informers.

The sentiment of legality was being stamped out of the public conscience, and with it religion and morality. 'Bishops have been heard to preach civil war—a crusade against the Liberals; priests seem to mix themselves in wretched party strife, egging on the mob to vent its worst passions.(This type of behaviour has never really ceased on the part of the Catholic church who to the present day are involved with things that are in no way the work of God.That said there are those that still believe in God's love.The real point is that the organisation has always been corrupt and all the time offers false testimony to the truth,its present involvement with real estate and its partiality to the politics of particular groups in Italy and other places show that much of the following it gets is merely propaganda and good P.R.)

There is not a Catholic country in which the really Christian priest is so rarely found as in the States of the Church.'

If Gregory XVI. was not without reasons for disquietude in his last hours, he could take comfort in the fact that he had succeeded in keeping railways out of all parts of his dominions.

Gas and suspension bridges were also classed as works of the Evil One, and vigorously tabooed.

Among the Pope's subjects there was a young prelate who had never been able to make out what there was subversive to theology in a steam-engine, or why the safety of the Papal government should depend on its opposing every form of material improvement, although in discussing these subjects he generally ended by saying: 'After all I am no politician, and I may be mistaken.'

This prelate was Cardinal Mastai-Ferretti, Bishop of Imola.

Born in 1792 at Sinigaglia, of a good though rather needy family, Count Giovanni Maria Mastai was piously brought up by his mother, who dedicated him at an early age to the Virgin, to whom she believed that she owed his recovery from an illness which had been pronounced fatal.

Roman Catholic writers connect the promulgation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception with this incident of childhood. After entering the priesthood, young Mastai devoted most of his energies to active charity, and remained, as he said, 'no politician,' being singularly ignorant of the world and of public affairs, though full of amiable wishes that everyone should be happy.

His chief friends in his Romagnol diocese, friends on the intimate basis of social equality and common provincial interests, were sound patriots, though not revolutionists, and the future Pio Nono involuntarily adopted their ideas and sympathies.

He saw with his eyes certain abuses so glaring that they admitted of no two opinions, and these helped to convince him of the truth of his friends' arguments in favour of a completely new order of things.

One such abuse was the encouragement given by government , the Vatican, to the Society of the Centurioni, the latest evolution of the Calderai; the Centurions, recruited among roughs and peasants, were set upon the respectable middle classes, over which they tyrannised by secret accusations or open violence: it was well understood that anyone called a Liberal, or Freemason, or Carbonaro could be beaten or killed without inquiries being made.And the Pope and the Church sanctioned it fully.

Gioberti indicated the Supreme Pontiff as the natural head of the Italian Union, and the King of Sardinia as Italy's natural deliverer from foreign domination

The Conclave opened on the 14th of June 1846. He was, in fact, elected after the Conclave had lasted only two days, while the Conclave which elected his predecessor lasted sixty-four.

The brevity of that to which Pius IX became pope was that no one wanted one who would be ruled from Vienna, it was done quick to avoid germanic influence

On the night of the 6th of December 1846, the whole line of the Apennines from Liguria to Calabria was illuminated. A hundred years before, a stone thrown by the child Balilla had given the signal for the expulsion of the Austrians from Genoa: this was the memory flashed from height to height by countless beacons, but while celebrating the past, they were the fiery heralds of a greater revolution.

The upheaval of Europe did not become a fact, however, for another year. Meantime, the Roman States attracted more attention than any other part of the peninsula, from the curiosity awakened by the progress of the experiment of which they were the scene.

swiss papal regiment 1848. The Swiss have had a miserable history as regards their call to arms for their are none lower than the mercenary It is not doubtful that at the first moment Pius IX. was under the impression that the problem he had taken in hand was eminently simple.

swiss papal regiment 1848. The Swiss have had a miserable history as regards their call to arms for their are none lower than the mercenary It is not doubtful that at the first moment Pius IX. was under the impression that the problem he had taken in hand was eminently simple.

A little goodwill on the part of everybody, an amnesty to heal old sores, and a few administrative reforms, ought, he thought, to set everything right

Now what had been going on for years in the Roman States was not the process of gradual growth, but the process of rapid disintegration.

The Temporal Power of the Popes had died without anyone noticing it

Every foreigner in Rome during the reign of Gregory XVI. bore witness that his government depended for its existence absolutely on the Swiss Guards.

In 1845, Count Rossi told Guizot that without the Swiss regiments the government in the Legations and the Marches 'would be overthrown in the twinkling of an eye.'

In the course of the summer of 1847, the Prince metternich said more than once to the British Ambassador: 'The Emperor is determined not to lose his Italian dominions.' It was no idle boast.

He believed that Austria's only enemy was the aristocracy. He even threw out hints that if the Austrian Government condescended to do so, it could raise a social or peasants' war of the country people against their masters. This is the policy which has been elaborately followed by the Russians in Poland.

On the other hand, he was strictly correct in his estimate of the patriotism of the aristocracy. The fact always seemed to the Prince a violation of eternal laws. According to him, the fore-ordained disaffected in every country were drawn from the middle classes. What business had noblemen to prefer revolution to their riches he thought and he was right. The rich liberal always wants the poor to pick up his bill whether the poor gives a shit or no.

lovers in war

Towards the end of 1847, there was a curious shuffling of the cards in the small states of Lucca and Parma, resulting in much irritation, which, in an atmosphere so charged with revolutionary electricity, was not without importance.

The dissolute Bourbon prince who reigned in Lucca, Charles Ludovico, had but one desire, which was to increase his civil list.

He hit upon an English jockey named Ward, who came to Italy in the service of a German count, and this person he made his Chancellor of the Exchequer.

By various luminous strokes, Ward furthered his Sovereign's object without much increasing the taxation, and when matters began to grow complicated, he proposed the sale of the Duchy to Tuscany, with which it would, in any case, be united, when, on the death of the ex-Empress Marie-Louise, the Duchy of Parma devolved on the Duke of Lucca.

At the same time, by a prior agreement, a district of Tuscany called the Lunigiana was consigned, one-half to the Duchess of Parma, and the other to the Duke of Modena. The indignation of the population, which was made, by force, subject to the Duke of Modena, was intense, and the whole transaction of handing about Italians to suit the pleasure of princes, or to obey the articles of forgotten treaties, reminded the least sensitive of the everyday opprobrium of their lot.

The bargain with Tuscany had been struck only eight days when Marie-Louise died—unlamented, since the latter years of her reign formed a sad contrast to the earlier. Marie-Louise had not a bad disposition, but she always let her husband of the hour govern as he chose; of the four or five of these husbands, the last two, and particularly the hated Count de Bombelles, undid all the good done by their more humane predecessors.

The Parmese petitioned their new Duke to send the man away, and to grant them some measure of freedom.

The answer he gave was the confirmation of Bombelles in all his honours, and the conclusion of a treaty with Austria, securing the assistance of her arms.

A military force had been sent to Parma to escort the body of the late Duchess to Vienna; but on the principle that the living are of more consequence than the dead, it remained there to protect the new Duke from his subjects.

Marie-Louise and her lovers, Charles Ludovico and his jockey-minister, are instructive illustrations of the scandalous point things had reached in the small states of Italy.

There was, indeed, one state in which, though the dynasty was Austrian, the government was conducted without ferocity and without scandal.

This was Tuscany. The branch of the Hapsburg-Lorraine family established in Tuscany produced a series of rulers who, if they exhibited no magnificent qualities, were respectable as individuals, and mild as rulers.

Giusti dubbed Leopold II. 'the Tuscan Morpheus, crowned with poppies and lettuce leaves,' and the clear intelligence of Ricasoli was angered by the languid, let-be policy of the Grand-Ducal government, but, compared with the other populations of Italy, the Tuscans might well deem themselves fortunate. Only on one occasion had the Grand Duke given up a fugitive from the more favoured provinces, and the presence of distinguished exiles lent brilliancy to his capital. Leopold II. hesitated between the desire to please his subjects and the fear of his Viennese relations, who sent him through Metternich the ominous reminder, 'that the Italian Governments had only subsisted for the last ten years by the support they received from Austria'—an assertion at which Charles Albert took umbrage, but he was curtly told that he was not intended. In spite of his fears, however, the Grand Duke instituted a National Guard on the 4th of September, which was correctly judged the augury of further concessions. In August, the Austrian Minister had distinctly threatened to occupy Tuscany, or any other of the Italian duchies where a National Guard was granted; its institution was therefore interpreted as a decisive act of rebellion against the Imperial dictatorship. The red, white and green tricolor, not yet permitted in Piedmont, floated already from all the towers of the city on the Arno.

Where there were no signs of improvement was in the government of the Two Sicilies. King Ferdinand undertook a journey through several parts of the country, but as Lord Napier, the British Minister, expressed it: 'Exactly where the grace of the royal countenance was principally conferred, the rebels sprung up most thickly.' A revolution was planned to break out in all the cities of the kingdom, but the project only took effect at Messina and at Reggio, and in both places the movement was stifled with prompt and barbarous severity. When the leader of the Calabrian attempt, Domenico Romeo, a landed proprietor, was caught on the heights of Aspromonte, his captors, after cutting off his head, carried it to his young nephew, whom they ordered to take it to Reggio with the cry of 'Long live the King.' The youth refused, and was immediately killed. In the capital, Carlo Poerio and many patriots were thrown into prison on suspicion. Settembrini had just time to escape to Malta.

The year 1847 closed amid outward appearances of quiet.On the 12th of January, the birthday of the King of the Two Sicilies, another insurrection broke out in Sicily; this time it was serious indeed. The City of the Vespers lit the torch which set Europe on fire.

So began the year of revolution which was to see the kings of the earth flying, with or without umbrellas, and the principle of monarchy more shaken by the royal see-saw of submission and vengeance than ever it was by the block of Whitehall or the guillotine of the Place Louis XV.

In Italy, the errors and follies of that year were not confined to princes and governments, but it will remain memorable as the time when the Italian nation, not a dreamer here or there, or a handful of heroic madmen, or an isolated city, but the nation as a whole, with an unanimity new in history, asserted its right and its resolve to exist.

King Ferdinand sent 5000 soldiers to 'make a garden,' as he described it, of Palermo, if the offers sent at the same time failed to pacify the inhabitants. These offers were refused with the comment: 'Too late,' and the Palermitans prepared to resist to the death under the guidance of the veteran patriot Ruggiero Settimo, Prince of Fitalia. 'Separation,' they said, 'or our English Constitution of 1812.' Increased irritation was awakened by the discovery in the head office of the police at Palermo of a secret room full of skeletons, which were supposed to belong to persons privately murdered. The Neapolitans were compelled to withdraw with a loss of 3000 men, but before they went, the general in command let out 4000 convicts, who had been kept without food for forty-eight hours. The convicts, however, did not fulfil the intentions of their liberator, and did but little mischief. Not so the Neapolitan troops, who committed horrors on the peasantry as they retreated, which provoked acts of retaliation almost as barbarous. In a short time all Sicily was in its own hands except the citadel of Messina.

It is not possible to follow the Sicilians in their long struggle for their autonomy. They stood out for some fourteen months. An English Blue-book is full of the interminable negotiations conducted by Lord Napier and the Earl of Minto in the hope of bringing the strife to an end. When the parliament summoned by the revolutionary government declared the downfall of the House of Bourbon, all the stray princes in Europe, including Louis Napoleon, were reviewed as candidates for the throne. The choice fell on the Duke of Genoa; it was well received in England, and the British men-of-war were immediately ordered to salute the Sicilian flag. But the Duke's reign never became a reality. After an heroic struggle, the islanders were subjugated in the spring of 1849.

So stout a fight for independence must win admiration, if not approval. The political reasons against the course taken by the Sicilians have been suggested in a former chapter. In separating their lot from that of Naples, in rejecting even freedom unless it was accompanied by disruption, they hastened the ruin of the Neapolitans and of themselves, and surely played into the hands of the crafty tyrant who desired nothing better than to fish in the troubled waters of his subjects' dissensions.

In the gathering storm of January 1848, the first idea that occurred to Ferdinand II. was the good old plan of calling in Austrian assistance.

But the Austrians were told by Pius IX. that he would not allow their troops to pass through his territory. Had they attempted to pass in spite of his warning, events would have taken a different turn, as the Pope would have been driven into a war with Austria then and there; perhaps he would have been glad, as weak people commonly are, of the compulsion to do what he dared not do without compulsion. The Austrian Government was too wise to force a quarrel; it was easy to lock up Austrian subjects for crying 'Viva Pio Nono,' but the enormous importance of keeping the Head of the Church, if possible, in a neutral attitude could not be overlooked. All thoughts of going to Ferdinand's help were politely abandoned, and he, seeing himself in a defenceless position, and pondering deeply on the upsetting of Louis Philippe's throne, which was just then the latest news, decided on that device, dear to all political conjurors, which is known as taking the wind out of your enemy's sails. The Pope, the Grand Duke of Tuscany and the King of Sardinia, had worried him for six months with admonitions. 'Very well,' he now said; 'they urge me forward, I will precipitate them.' Constitution, representative government, unbridled liberty of the press, a civic guard, the expulsion of the Jesuits; what mattered a trifle more or less when everything could be revoked at the small expense of perjury? Ferdinand posed to perfection in the character of Citizen King. He reassured those who ventured to show the least signs of apprehension by saying: 'If I had not intended to carry out the Statute, I should not have granted it.'

Not many days later, the Grand Duke of Tuscany and the King of Sardinia each promulgated a Charter. In the case of Charles Albert, it had been formally promised on the 8th of February, after sleepless nights, severe fasts, much searching of the heart—contrasting strangely with the gay transformation scene at Naples; but promises have a more serious meaning to some persons than to others. Nor did Charles Albert take any pleasure in the shouts of a grateful people. 'Born in revolution,' he once wrote, 'I have traversed all its phases, and I know well enough what popularity is worth—viva to-day, morte to-morrow.'

In the Lombardo-Venetian provinces all seemed still quiet, but the brooding discontent of the masses increased with the increasing aggressiveness of the Austrian soldiers, while the refusal to grant the studiously moderate demands of men like Nazari of Bergamo and Manin and Tommasco of Venice, who were engaged in a campaign of legal agitation, brought conviction to the most cautious that no measure of political liberty was obtainable under Austrian rule.

At the Scala Theatre some of the audience had raised cries of 'Viva Pio Nono' during a performance of I Lombardi This was the excuse for prohibiting every direct or indirect public reference to the reigning Pontiff. Nevertheless, a few young men were caught singing the Pope's hymn, upon which the military charged the crowd. On the 3rd of January the soldiers fell on the people in the Piazza San Carlo, killing six and wounding fifty-three. The parish priest of the Duomo said that he had seen Russians, French and Austrians enter Milan as invaders; but a scene like that of the 3rd of January he had never witnessed; 'they simply murdered in the streets.'

The Judicium Statuarium, equivalent to martial law, was proclaimed in February; but the Viennese revolution of the 8th of March, and Prince Metternich's flight to England, were followed by promises to abolish the censure, and to convoke the central congregations of the Lombardo-Venetian kingdom. The utmost privilege of these assemblies was consultative. In 1815 they were invested with the right to 'make known grievances,' but they had only once managed to perform this modest function. It was hardly worth while to talk about them on the 18th of March 1848.

On the morning of that day, Count O'Donnel, the Vice-Governor of Milan, announced the Emperor's concessions. Before night he was the hostage of the revolution, signing whatever decrees were demanded of him till in a few hours even his signature was dispensed with. The Milanese had begun their historic struggle.

Taking refuge in the Citadel, Radetsky wrote to the Podestà, Count Gabrio Casati (brother of Teresa Confalonieri), that he acknowledged no authority at Milan except his own and that of his soldiers. Those who resisted would be guilty of high treason. If arguments did not avail, he would make use of all the means placed in his hands by an army of 100,000 men to bring the rebel city to obedience. Unhappily for Radetsky, there were not any such 100,000 men in Italy, though long before this he had told Metternich that he could not guarantee the safety of Lombardy with less than 150,000. In spite of partial reinforcements, the number did not amount to more than from 72,000 to 75,000, while at Milan it stood at between 15,000 and 20,000. But if we take the lower estimate, 15,000 regular troops under such a commander, who, most rare in similar emergencies, knew his own mind, and had no thought except the recovery of the town for his Sovereign, constituted a formidable force against a civilian population, which began the fight with only a few hundred fowling-pieces. The odds on the side of Austria were tremendous.

If the Milan revolt had been one of the customary revolutions, arranged with the help of pen and paper, its first day would have been certainly its last. But even more than the Sicilian Vespers, it was the unpremeditated, irresistible act of a people sick of being slaves. At the beginning Casati tried to restrain it; so, with equal or still stronger endeavours, did the republican Carlo Cattaneo, whose influence was great. 'You have no arms,' he said again and again. Not a single man of weight took upon himself the awful responsibility of urging the unarmed masses upon so desperate an enterprise; but when the die was cast none held back. Initiated by the populace, the revolt was led to its victorious close by the nerve and ability of the influential men who directed its course.

Towards nightfall on the 18th, during which day there had been only scuffles between the soldiers and the people, Radetsky took the Broletto, where the Municipality sat, after a two hours' siege, and sent forthwith a special messenger to the Emperor with the news that the revolution was on a fair way to being completely crushed. Meanwhile, he massed his troops at all the entrances to the city, so that at dawn he might strangle the insurrection by a concentric movement, as in a noose. The plan was good; but to-morrow does not belong even to the most experienced of Field-Marshals.

In all quarters of the city barricades sprang up like mushrooms. Everything went, freely given, to their construction; the benches of the Scala, the beds of the young seminarists, the court carriages, found hidden in a disused church, building materials of the half-finished Palazzo d'Adda, grand pianofortes, valuable pieces of artistic furniture, and the old kitchen table of the artisan. Before the end of the fight the barricades numbered 1523.

Young nobles, dressed in the velvet suits then in vogue, cooks in their white aprons, even women and children, rushed to the defence of the improvised fortifications. Luciano Manara and other heroes, who afterwards fell at Rome, were there to lead. In the first straits for want of arms the museums of the Uboldi and Poldi-Pozzoli families were emptied of their rare treasures by permission of the owners; the crowd brandished priceless old swords and specimens of early firearms. More serviceable weapons were obtained by degrees from the Austrian killed and wounded, and from the public offices which fell into their hands. Bolza, long the hated agent of the Austrian police, was discovered by the people, but they did not harm him. Throughout the five days, the Milanese showed a forbearance which was the more admirable, because there can be no doubt that when the Austrians found they were getting the worst of it, they vented their rage in deplorable outrages on non-combatants. That Radetsky was personally to blame for these excesses has never been alleged, and it was perhaps beyond the power of the officers to keep discipline among soldiers who, towards the end, were wild with panic.

'The very foundations of the city were torn up,' wrote the Field-Marshal in his official report; 'not hundreds, but thousands of barricades crossed the streets. Such circumspection and audacity were displayed that it was evident military leaders were at the head of the people. The character of the Milanese had become quite changed. Fanaticism had seized every rank and age and both sexes.'

As always happens with street-fighting, the number of the slain has never been really known; the loss of the citizens was small compared with that of the Austrians, who, according to some authorities, lost 5000, between killed and wounded.

Radetsky ordered the evacuation of the town and citadel on the night of Wednesday, the 22nd of March. The Milanese had won much more than freedom—they had won the right to it. And what they had done they had done alone. When the news that the capital was up in arms spread through Lombardy, there was but one gallant impulse, to fly to its aid. But the earliest to arrive, Giuseppe Martinengo Cesaresco, with his troop of Brescian peasants, found when he reached Milan that they were a few hours too late to share in the last shots fired upon the retreating Austrians.

Nowhere, except in Milan, did the revolution meet with a Radetsky. The Austrian authorities became convinced that their position was untenable, and they desired to avoid a useless sacrifice of life. This, rather than cowardly fears, was the motive which induced Count Palffy and Count Zichy, the civil and military governors of Venice, to yield the city without deluging it in blood. The latter had been guilty of negligence in leaving the Venetian arsenal in charge of troops so untrustworthy that Manin could take it on the 22nd of March by a simple display of his own courage, and without striking a blow, but after this first success on the side of the revolution, which supplied the people with an unlimited stock of arms and ammunition, the Austrians did well to give way even from their own point of view. At seven o'clock on the evening of the 22nd of March, the famous capitulation was signed. Manin's prediction of the previous day, 'To-morrow the city will be in my power, or I shall be dead,' had been realised in the first alternative.

Daniel Manin, who was now forty-four years of age, was by profession a lawyer, by race a Jew. His father became a Christian, and, according to custom, took the surname of his godfather, who belonged to the family of the last Doge of Venice.

Manin and the Dalmatian scholar, Niccolò Tommaseo, had been engaged in patiently adducing proof after proof that Austria did not even abide by her own laws when the expression of political opinion was concerned. At the beginning of the revolution they were in prison, and Palffy's first act of surrender was to set them free. Henceforth Manin was undisputed lord of the city. It is strange how, all at once, a man who was only slightly known to the world should have been chosen as spokesman and ruler. It did not, however, happen by chance. The people in Italy are observant; the Venetians had observed Manin, and they trusted him. The power of inspiring trust was what gave this Jewish lawyer his ascendancy, not the talents which usually appeal to the masses. He had not the advantage of an imposing presence, for he was short, slight, with blue eyes and bushy hair; in all things he was the opposite to a demagogue; he never beguiled, or flattered, or told others what he did not believe himself. But, on his side, he knew the people, whom most revolutionary leaders know not at all. 'That is my sole merit,' he used to say. It was that which enabled him to cleanse Venice from the stain of having bartered her freedom for the smile of a conqueror, and give her back the name and inheritance of 'eldest child of liberty.'

It was a matter of course that emancipated Venice should assume a republican form of government. Here the republic was a restoration. At Milan the case was different; there were two parties, that of Cattaneo, which was strongly republican, that of Casati, which was strongly monarchical. There was a third party, which thought of nothing except of never again seeing a soldier with a white coat. By mutual agreement, the Provisional Government declared that the decision as to the form of government should be left to calmer days. For a time this compromise produced satisfactory results.

The revolution gained ground. Francis of Modena executed a rapid flight, and the Duke of Parma presently followed him. By the end of March, Lombardy and Venetia were free, saving the fortresses of the Quadrilateral. The exception was of far greater moment than, in the enchantment of the hour, anyone dreamt of confessing. Mantua, Legnano, Peschiera and Verona were so many cities of refuge to the flying Austrian troops, where they could rest in safety and nurse their strength. Still, the results achieved were great, almost incredible; with the expectation that Rome, Naples, Tuscany and Piedmont would send their armies to consolidate the work already done, it was natural to think that, whatever else might happen, Austrian dominion was a thing of the past. Alessandro Bixio (brother of the General), who was a naturalised Frenchman, wrote to the French Government on the 7th of April from Turin: 'In the ministries, in meetings, in the streets, you only see and hear people to whom the question of Italian independence seems to be one of those historical questions about which the time is past for talking. According to the general opinion, Austria is nothing but a phantom, and the army of Radetsky a shadow.' Such were the hopes that prevailed. They were vain, but they did not appear so then.

Pius IX. seemed to throw in his lot definitely with the revolution when, on the 19th of March, he too granted a Constitution, having previously formed a lay ministry, which included Marco Minghetti and Count Pasolini, under the presidency of Cardinal Antonelli, who thus makes his first appearance as Liberal Premier. That the Roman Constitution was an unworkable attempt to reconcile lay and ecclesiastical pretensions, that the proposed Chamber of Deputies, which was not to make laws affecting education, religious corporations, the registration of births and marriages; or to confer civil rights on non-catholics, or to touch the privileges and immunities of the clergy, might have suited Cloud-cuckoo-town, but would not suit the solid earth, were facts easy to recognise, but no one had time to pause and consider. It was sufficient to hear Pius proclaim that in the wind which was uprooting oaks and cedars might be clearly distinguished the Voice of the Lord. Such utterances, mingled with blessings on Italy, brought balm to patriotic souls. The Liberals had no fear that the Pope would veto the participation of his troops in the national war, for they were blind to the complications with which a fighting Pope would find himself embarrassed in the middle of the nineteenth century. But the other party discerned these complications from the first, and knew what use to make of them.

The powers of reaction had only to catch hold of a perfectly modern sentiment, the doctrine that ecclesiastics should be men of peace, in order to dissipate the myth of a Pope liberator. It was beside the question that, from the moment he accepted such a doctrine, the Pope condemned the institution of prince-bishoprics, of which he represented the last survival. Nor was it material that, if he adopted it, consistency should have made him carry it to its logical consequence of non-resistance. By aid of this theory of a peaceful Pontiff, with the threat, in reserve, of a schism, Austria felt confident that she could avoid the enormous moral inconvenience of a Pope in arms against her.

Either, however, the full force of the influence which caused Pius IX. to draw back was not brought to bear till somewhat late in the day, or the part acted by him during the months of March and April can be hardly acquitted of dissimulation. War preparations were continued, with the warm co-operation of the Cardinal President of the Council, and when General Durando started for the frontier with 17,000 men, he would have been a bold man who had said openly in Rome that they were intended not to fight.

While the Pope was still supposed to favour the war, Ferdinand of Naples did not dare to oppose the enthusiasm of his subjects, and the demand that a Neapolitan contingent should be sent to Lombardy. The first relay of troops actually started, but the generals had secret orders to take the longest route, and to lose as much time as possible.

Tuscany had a very small army, but such assistance as she could give was both promised and given. The fate of the Tuscan corps of 6000 men will be related hereafter. The Grand Duke Leopold identified himself with the Italian cause with more sincerity than was to be found at Rome or Naples; still, the material aid that he could offer counted as next to nothing.

There remained Piedmont and Charles Albert. Now was the time for the army which he had created (for Charles Felix left no army worthy of the name) to assert upon the Lombard fields the reason of its existence. War with Austria was declared on the 23rd of March. It was midnight; a vast crowd waited in silence in Piazza Castello. At last the windows of the palace were opened, a sudden flood of light from within illuminating the scene. Charles Albert stepped upon the balcony between his two sons. He was even paler than usual, but a smile such as no one had seen before was on his lips. He waved the long proscribed tricolor slowly over the heads of the people.

The King said in his proclamation that 'God had placed Italy in a position to provide for herself ('in grado di fare da sè'). Hence the often repeated phrase: 'L'Italia farà da sè.' He told the Lombard delegates, who met him at Pavia that he would not enter their capital, which had shown such signal valour, till after he had won a victory.

He declared to all that his only aim was to complete the splendid work of liberation so happily begun; questions of government would be reserved for the conclusion of the war. Joy was the order of the day, but the fatal mistakes of the campaign had already commenced; there had been inexcusable delay in declaring war; if it was pardonable to wait for the Milanese initiative, it was as inexpedient as it seemed ungenerous to wait till the issue of the struggle at Milan was decided.

Then, after the declaration of war, considering that the Sardinian Government must have seen its imminence for weeks, and indeed for months, there was more time lost than ought to have been the case in getting the troops under weigh. Still, at the opening of the campaign, two grand possibilities were left. The first was obviously to cut Radetsky off in his painful retreat, largely performed along country by-roads, as he had to avoid the principal cities which were already free.

Had Charles Albert caught him up while he was far from the Quadrilateral, the decisive blow would have been struck, and the only man who could save Austria in Italy would have been taken prisoner.

Radetsky chose the route of Lodi and the lower Brescian plains to Montechiaro, where the encampments were ready for the Austrian spring manoeuvres: from this point an easy march carried him under the walls of Verona.

Here he met General d'Aspre (below), who had just arrived with the garrison of Padua. D'Aspre, by skill and resolution, had brought his men from Padua without losing one, having refused the Paduans arms for a national guard, though ordered from Milan to grant them. 'You come to tell me all is lost,' said the Field-Marshal when they met 'No,' rejoined the younger general, 'I come to tell you all is saved.'

This great chance missed, there was another which could have been seized. Mantua, extraordinary to relate, was defended by only three hundred artillerymen and a handful of hussars. It would have fallen into the hands of its own citizens but for the presence of mind of its commandant, the Polish General Gorzhowsky, who told them that to no one on earth would he deliver the keys of the fortress except to his Emperor, and that the moment he could no longer defend it he would blow it into the air, with himself and half Mantua. He showed them the flint and the steel with which he intended to do the deed. Enemy though he was, that incident ought to be recorded in letters of gold on the gates of Mantua, as a perpetual lesson of that most difficult thing for a country founded in revolution to learn: the meaning of a soldier's duty.

It would have fallen into the hands of its own citizens but for the presence of mind of its commandant, the Polish General Gorzhowsky, who told them that to no one on earth would he deliver the keys of the fortress except to his Emperor, and that the moment he could no longer defend it he would blow it into the air, with himself and half Mantua. He showed them the flint and the steel with which he intended to do the deed. Enemy though he was, that incident ought to be recorded in letters of gold on the gates of Mantua, as a perpetual lesson of that most difficult thing for a country founded in revolution to learn: the meaning of a soldier's duty.

It is easy to see that, if Charles Albert had made an immediate dash on Mantua, the fortress, or its ruins, would have been his, to the enormous detriment of the Austrian position. But this chance too was missed. On the 31st of March, the 9000 men sent with all speed by Radetsky to the defenceless fortress arrived, and henceforth Mantua was safe. Charles Albert only got within fifteen or sixteen miles of it five days later, to find that all hope of its capture was gone.

The campaign began with political as well as with military mistakes. At the same time that the King of Sardinia was declaring in the Proclamation addressed to the Lombards that, full of admiration of the glorious feats performed in their capital, he came to their aid as brother to brother, friend to friend, his ambassadors were trying to persuade the foreign Powers, and especially Austria, Prussia and Russia, that the only object of the war was to avoid a revolution in Piedmont, and to prevent the establishment of a republic in Lombardy. No one was convinced or placated by these assurances; far better as policy than so ignominious an attempt at hedging would have been the acknowledgment to all the world of the noble crime of patriotism. But, as Massimo d'Azeglio once observed, Charles Albert had the incurable defect of thinking himself cunning. It was, moreover, only too true that, although in these diplomatic communications the King allowed the case against him to be stated with glaring exaggeration, yet they contained an element of fact. He was afraid of revolution at home; he was afraid of a Lombard republic; these were not the only, nor were they the strongest, motives which drove him into the war, but they were motives which, associated with deeper causes, contributed to the disasters of the future.

The Piedmontese force was composed of two corps d'armée, the first under General Bava and the second under General Sonnaz: each amounted to 24,000 men. The reserves, under the Duke of Savoy, numbered 12,000. Radetsky, at first (after strengthening the garrisons in the fortresses), could not put into the field more than 40,000 men. As has been stated, the King assumed the supreme command, which led to a constant wavering between the original plan of General Bava, a capable officer, and the criticisms and suggestions of the staff. The greatest mistake of all, that of never bringing into the field at once more than about half the army, was not without connection with the supposed necessity, based on political reasons, of garrisoning places in the rear which might have been safely left to the care of their national guards.

Besides the royal army, there were in the field 17,000 Romans, 3000 Modenese and Parmese, and 6000 Tuscans. There were also several companies of Lombard volunteers, Free Corps, as they were called, which might have been increased to almost any extent had they not been discouraged by the King, who was believed to look coldly on all these extraneous allies, either from doubt of their efficiency, or from the wish to keep the whole glory of the campaign for his Piedmontese army.

The first engagements were on the line of the Mincio. On the 8th of April the Sardinians carried the bridge of Goito after a fight of four hours. The burning of the village of Castelnuovo on the 12th, as a punishment for its having received Manara's band of volunteers, excited great exasperation; many of the unfortunate villagers perished in the flames, and this and other incidents of the same kind did much towards awakening a more vivid hatred of the Austrians among the peasants.

After easily gaining possession of the left (Venetian) bank of the Mincio, Charles Albert employed himself in losing time over chimerical operations with a view to taking the fortresses of Peschiera and Mantua, now strongly garrisoned, and impregnable while their provisions lasted.

This object governed the conduct of the campaign, and caused the waste of precious months during every day of which General Nugent, with his 30,000 men, was approaching one step nearer from the mountains of Friuli, and General Welden, with his 10,000, down the passes of Tyrol. If, instead of playing at sieges, Charles Albert had cut off these reinforcements, Radetsky would have been rendered powerless, and the campaign would have had another termination. Never was there a war in which the adoption of Napoleon's system of crushing his opponents one by one, when he could not outnumber them if united, was more clearly indicated.

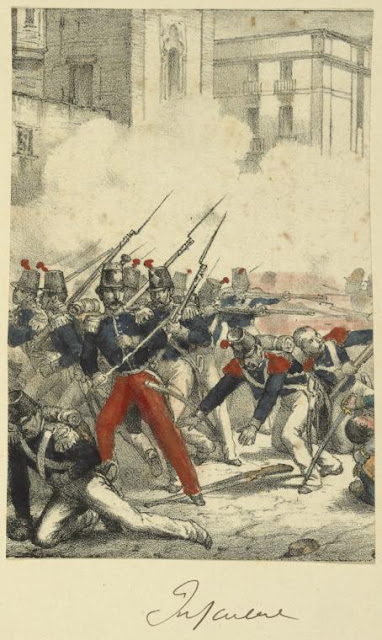

54mm

54mm battleThe battle of Goito was the opening salvo of the battle for Italy. Charles Albert the Italian king met the Austrians here and tried to force the bridges at Goito and Monzambano to cross the Ticino.The Austrians fled after a fierce firefight and the new Italian army had gained their first victory.

battleThe battle of Goito was the opening salvo of the battle for Italy. Charles Albert the Italian king met the Austrians here and tried to force the bridges at Goito and Monzambano to cross the Ticino.The Austrians fled after a fierce firefight and the new Italian army had gained their first victory.

sardinian Grenadiers

sardinian Grenadiers

Bersaglieri at Goito

Bersaglieri at Goito

Superb model from Castel

It was a "locanda " like this that stood on the banks at the river at Goito where the Bersaglieri first attacked the Austrians. I'm still looking for the actual place

The Piedmontese King Charles Albert. A near religous fanatic who is supposed to have put all down to the Lord's intervention.Who am I to deny that?

The Piedmontese King Charles Albert. A near religous fanatic who is supposed to have put all down to the Lord's intervention.Who am I to deny that?

The Sardinian Grenadiers at Goito in the province of Modena

The Sardinian Grenadiers at Goito in the province of Modena

The Sardinians had fought in the Crimean but few returned

The Sardinians had fought in the Crimean but few returned

Goito. Here is where a lot of the battle was fought in this opening round

Goito. Here is where a lot of the battle was fought in this opening round

A watercolour of the village

A watercolour of the village

Officer uniform of the Sardinian Grenadiers

Officer uniform of the Sardinian Grenadiers

Another officer tunic

Another officer tunic

Uniforms of the Sardinian Grenadiers

A print of the battle

A print of the battle

The river at Goito

The river at Goito

An old Liebig card rememebering the battle

This was where the Bersaglieri made their namesThe battle of Goito was the opening salvo of the battle for Italy. Charles Albert the Italian king met the Austrians here and tried to force the bridges at Goito and Monzambano to cross the Ticino.The Austrians fled after a fierce firefight and the new Italian army had gained their first victory.

above is a building that is on sale at the moment in the village of Goito. It dates from the times of the battle. Its a good idea for wargames scenary if you intend building one

The battle of Goito near Modena sounded the first salvos of what would be a long war between the Italians and Austrians. It was 1848 and all Europe was in revolution. The Italians wanted to throw off the yolk of Austrian demonstration and looked to independent Piedmont to lead them as their other choice the Pope held back.

The battle of Goito near Modena sounded the first salvos of what would be a long war between the Italians and Austrians. It was 1848 and all Europe was in revolution. The Italians wanted to throw off the yolk of Austrian demonstration and looked to independent Piedmont to lead them as their other choice the Pope held back.

Charles Albert arrived with his army and found the village near Modena defended by Austrians. The battle took place along the river which is about as wide as the Thames at Reading. It was a victory.Above are the Sardinian Grenadiers

an old man who was in such enfeebled health that his death was expected at the time of his election, but, like a more famous pontiff, he made a sudden recovery, which was attributed to the act of a prelate, who, in prayer, offered his own life for the Pope's, and who died a few days after resolving on the sacrifice.

an old man who was in such enfeebled health that his death was expected at the time of his election, but, like a more famous pontiff, he made a sudden recovery, which was attributed to the act of a prelate, who, in prayer, offered his own life for the Pope's, and who died a few days after resolving on the sacrifice.During this Pope's reign, the smallpox was rife in Rome, in consequence of the suppression of public vaccination. The next conclave, held in 1829, resulted in the election of Pius VIII. (Castiglioni da Cingoli),

who died on the 30th of November 1830, and was followed by Gregory XVI. (Cappellari). In each conclave,

who died on the 30th of November 1830, and was followed by Gregory XVI. (Cappellari). In each conclave,  Austria had secured the choice of a 'Zealot,' as the party afterwards called Ultramontane.

Austria had secured the choice of a 'Zealot,' as the party afterwards called Ultramontane.The last traces of reforms introduced by the French disappeared; criminal justice was again administered in secret; the police were arbitrary and irresponsible.

All over the Roman states, but especially in Romagna, the secret society of the Sanfedesti flourished exceedingly; whether, as is probable, an offshoot of the Calderai or of indigenous growth, its aims were the same.

(Sanfedesti were components of a popular movement anti-Republican fascism, the Sanfedisti in 1799 involved peasant masses and were the main exponents of banditry against the Neapolitan Republic; the movement was organized around the cardinal Fabrizio Dionigi Ruffo as Army of the Holy Faith in our Lord Jesus Christ)

The affiliated swore to spill the last drop of the blood of the Liberals, without regard to sex or rank, and to spare neither children nor old men. Many Romagnols had left their country after the abortive agitation of 1821, and amongst these were the Gamba family.

Count Pietro died in Greece, where he had gone on the service of freedom. Had he lived, this young man would have been sure to win a fair name in the annals of Italian patriotism; he should not, as it is, be quite forgotten, as it was chiefly due to him that Byron's life took the redeeming direction which led to Missolonghi.

In February 1831, Romagna and the Marches of Ancona threw off the Papal Government with an ease which must have surprised the most sanguine. The white, red and green tricolor was hoisted at Bologna, where, as far as is known, this combination of colours first became a political badge.

Thirty-six years before Luigi Zamboni and Gian Battista De Rolandis of Bologna had distributed rosettes of white, red and green ribbon; Zamboni was arrested, and strangled himself, afraid of betraying his friends; De Rolandis was hung on the 23rd of April 1796.

had distributed rosettes of white, red and green ribbon; Zamboni was arrested, and strangled himself, afraid of betraying his friends; De Rolandis was hung on the 23rd of April 1796.

Such was the origin of the flag, until 1831, the Carbonaro red, blue and black was the common standard of the revolution.

Count Pietro died in Greece, where he had gone on the service of freedom. Had he lived, this young man would have been sure to win a fair name in the annals of Italian patriotism; he should not, as it is, be quite forgotten, as it was chiefly due to him that Byron's life took the redeeming direction which led to Missolonghi.

In February 1831, Romagna and the Marches of Ancona threw off the Papal Government with an ease which must have surprised the most sanguine. The white, red and green tricolor was hoisted at Bologna, where, as far as is known, this combination of colours first became a political badge.

Thirty-six years before Luigi Zamboni and Gian Battista De Rolandis of Bologna

had distributed rosettes of white, red and green ribbon; Zamboni was arrested, and strangled himself, afraid of betraying his friends; De Rolandis was hung on the 23rd of April 1796.

had distributed rosettes of white, red and green ribbon; Zamboni was arrested, and strangled himself, afraid of betraying his friends; De Rolandis was hung on the 23rd of April 1796.rebellion

The 1st Battalion of Infantry of the line of 1814-1863 of the Duchy of Modena was reconstituted from a group of enthusiasts of local history of St. Possidonio (MO). Dr. Alberto Menziani says . "The flag is the faithful reproduction of that donated to the battalion in 1820 by the Duchess Maria Beatrice and commands and orders are drawn from the "Regulation of the exercise and Manoeuvres for the troops on foot of s.a.r. Francesco IV" the Ducal Army Estense of 1816."

The 1st Battalion of Infantry of the line of 1814-1863 of the Duchy of Modena was reconstituted from a group of enthusiasts of local history of St. Possidonio (MO). Dr. Alberto Menziani says . "The flag is the faithful reproduction of that donated to the battalion in 1820 by the Duchess Maria Beatrice and commands and orders are drawn from the "Regulation of the exercise and Manoeuvres for the troops on foot of s.a.r. Francesco IV" the Ducal Army Estense of 1816." The Group uniform 1814 blue with white pants and bolsters and 1850 became dark blue with grey trousers and white insignia. It is armed, like the Austrians, with the musket briquet muzzle English "Brown Bess" uniforms estensi are original designs of the era, in particular by the "Chronicle" by Antonio Rovatti Modonese uniform history is at the Archiviodi State of Modena and from research done by Dr.. Menziani

The rising at Parma requires but little comment. The Empress Marie-Louise above neither hated her subjects, nor was hated by them, but her engagements with Austria prevented her from granting the demanded concessions, and she abandoned her state, to return to it, indeed, under Austrian protection, but without the odious corollary of vindictive measures which was generally meant by a restoration.

Much more important is the history of the Modenese revolution.

Apologists have been found for the Bourbons of Naples, but, if anyone ever said a good word for Francesco d'Este,

it has escaped the notice of the present writer.

it has escaped the notice of the present writer.Under a despotism without laws (for the edicts of the Prince daily overrode the Este statute book which was supposed to be in force),

Modena was far more in the power of the priests, or rather of the Jesuits, than any portion of the states of the Church. Squint-eyed, crooked in mind and bloodthirsty, Francis was as ideal a bogey-tyrant as can be discovered outside fiction.

In 1822, he hung the priest Giuseppe Andreoli on the charge of Carbonarism; and his theory of justice is amusingly illustrated by the story of his sending in a bill to Sir Anthony Panizzi—who had escaped to England—for the expenses of hanging him in effigy.

Francis felt deeply annoyed by the narrow limits of his dominions, and his annoyance did not decrease with the decreasing chances of his ousting the Prince of Carignano from the Sardinian throne. He was intensely ambitious, and one of his subjects, a man, in other respects, of high intelligence, thought that his ambition could be turned to account for Italy. It was the mistake over again that Machiavelli had made with Cesare Borgia.

Ciro Menotti, who conceived the plan of uniting Italy under the Duke of Modena, was a Modenese landed proprietor who had exerted himself to promote the industry of straw-plaiting, and the other branches of commerce likely to be of advantage to an agricultural population.

He was known as a sound philanthropist, an excellent husband and father, a model member of society. Francis professed to take an interest in industrial matters; Menotti, therefore, easily gained access to his person.

In all the negotiations that followed, the Modenese patriot was supported and encouraged by a certain Dr Misley, who was of English extraction, with whom the Duke seems to have been on familiar terms.

It appears not doubtful that Menotti was led to believe that his political views were regarded with favour, and that he also received the royal promise that, whatever happened, his life would be safe.

This promise was given because he had the opportunity of saving the Duke from some great peril—probably from assassination, though the particulars were never divulged.

Misley went to Paris to concert with the Italian committee which had its seat there; the movement in Modena was fixed for the first days of February. But spies got information of the preparations, and on the evening of the 3rd, before anything had been done, Menotti's house was surrounded by troops, and after defending it, with the help of his friends, for two hours, he was wounded and captured. Next day the Duke despatched the following note to the Governor of Reggio-Emilia: 'A terrible conspiracy against me has broken out. The conspirators are in my hands. Send me the hangman.—Francis.'

Not all, however, of the conspirators were in his hands; the movement matured, in spite of the seizure of Menotti, and Francis, 'the first captain in the world,' as he made his troops call him, was so overcome with fright that on the 5th of February he left Modena with his family, under a strong military escort, dragging after him Giro Menotti, who, when Mantua was reached, was consigned to an Austrian fortress.

Meanwhile, the revolution triumphed. Modena chose one of her citizens as dictator, Biagio Nardi, who issued a proclamation in which the words 'Italy is one; the Italian nation is one sole nation,' testified that the great lesson which Menotti had sought to teach had not fallen on unfruitful ground. Wild as were the methods by which, for a moment, he sought to gain his end, his insistance on unity nevertheless gives Menotti the right to be considered the true precursor of Mazzini in the Italian Revolution.

Now that the testing-time was come, France threw to the winds the principle announced in her name with such solemn emphasis. 'Precious French blood should never be shed except on behalf of French interests,' said Casimir Périer, the new President of the Council.

A month after the flight of the Duke of Modena, the inevitable Austrians marched into his state to win it back for him. The hastily-organised little army of the new government was commanded by General Zucchi, an old general of Napoleon, who, when Lombardy passed to Austria, had entered the Austrian service.

He now offered his sword to the Dictator of Modena, who accepted it, but there was little to be done save to retire with honour before the 6000 Austrians. Zucchi capitulated at Ancona to Cardinal Benvenuti, the Papal delegate.

Those of the volunteers who desired it were furnished with regular passports, and authorised to take ship for any foreign port.

The most compromised availed themselves of this arrangement, but the vessel which was to bear Zucchi and 103 others to Marseilles, was captured by the Austrian Admiral Bandiera, by whom its passengers were kidnapped and thrown into Venetian prisons, where they were kept till the end of May 1832.

This act of piracy was chiefly performed with a view to getting possession of General Zucchi, who was tried as a deserter, and condemned to twenty years' imprisonment.

Among the prisoners was the young wife of Captain Silvestro Castiglioni of Modena. 'Go, do your duty as a citizen,' she had said, when her husband left her to join the insurrection. 'Do not betray it for me, as perhaps it would make me love you less.' She shared his imprisonment, but just at the moment of the release, she died from the hardships endured.

By the end of the month of March, the Austrians had restored Romagna to the Pope, and Modena to Francis IV. In Romagna the amnesty published by Cardinal Benvenuti was revoked, but there were no executions; this was not the case in Modena. The Duke brought back Ciro Menotti attached to his triumphal car, and when he felt that all danger was past, and that the presence of the Austrians was a guarantee against a popular expression of anger, he had him hung.

'When my children are grown up, let them know how well I loved my country,' Menotti wrote to his wife on the morning of his execution. The letter was intercepted, and only delivered to his family in 1848.

The revolutionists found it in the archives of Modena. On the scaffold he recalled how he was once the means of saving the Duke's life, and added that he pardoned his murderer, and prayed that his blood might not fall upon his head.

No sooner had the Austrians retired from the Legations in July 1831, than the revolution broke out again. Many things had been promised, nothing performed; disaffection was universal, anarchy became chronic, and was increased by the indiscipline of the Papal troops that were sent to put it down.

The Austrians returned and the French occupied Ancona, much to the Pope's displeasure, and not one whit to the advantage of the Liberals. This dual foreign occupation of the Papal states lasted till the winter of 1838.On 27 April 1831, Charles Albert came to the throne he had so nearly lost. His reconciliation with his uncle, Charles Felix, had been effected after long and melancholy preliminaries.

To wash off the Liberal sins of his youth, or possibly with a vague hope of finding an escape from his false position in a soldier's death, he joined the Duc d'Angoulême's expedition against the Spanish Constitutionalists.

Carlos Maria Isidro, Infante of Spain, the leader of the Carlist cause and pretender to the Spanish throne.