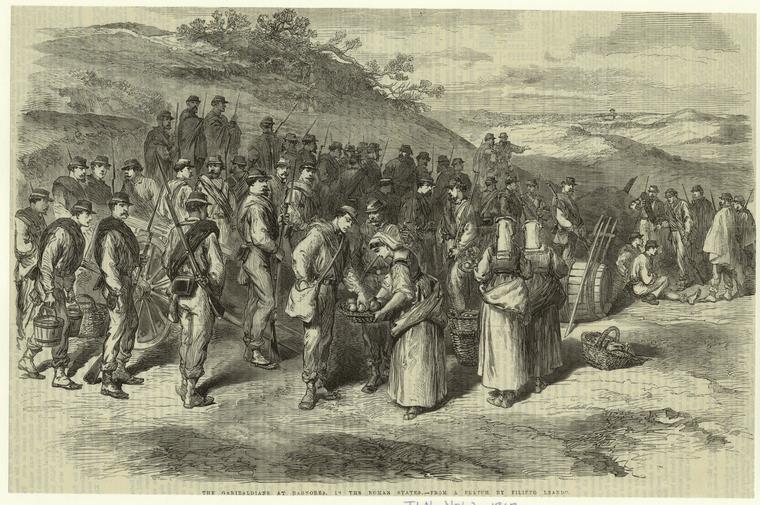

Mentana volunteers at bagnorea in lazio

Mentana volunteers at bagnorea in laziolies in a depression commanded by the neighbouring mounds, not a good configuration for defence. This village in the Roman Campagna sprang into history on a November day one thousand and sixty-seven years before, as the meeting-place of Charlemagne and Leo III. Here they shook hands over their bargain: that the Pope should crown the great Charles Emperor, and that the Emperor should assure to the Pope his temporal power. And now the ragged band of Italian youths was come to say that of bargains between Popes and Emperors there had been enough.

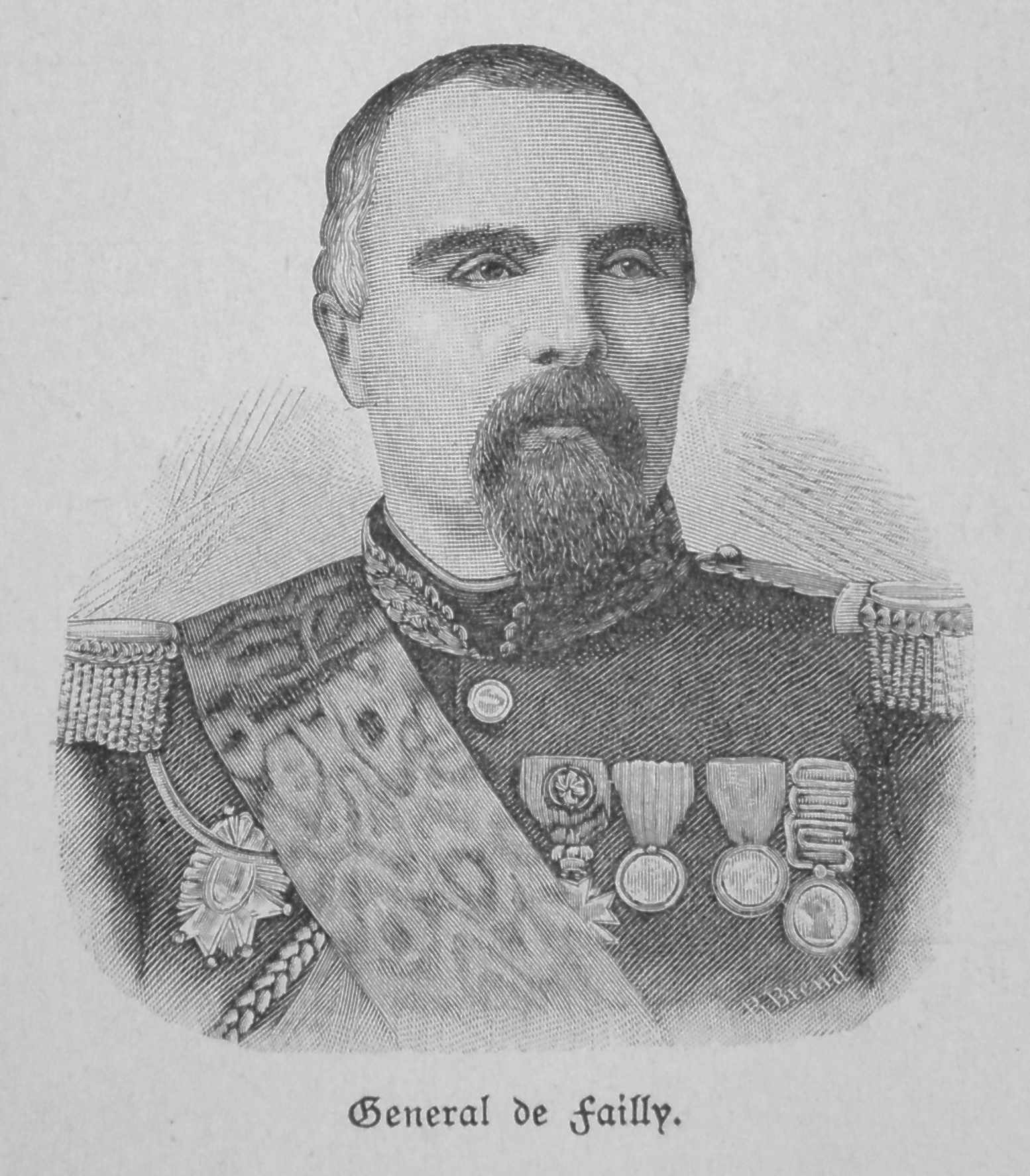

General De Failly

It was two o'clock. The enemy's fire slackened; something was going on which the volunteers could not make out. All at once there was a sharp unfamiliar detonation, resembling the whirring sound of a machine. The French had come into action.the rifle that defeated the Garibaldians was so called after its inventor, Antoine Alphonse Chassepot (1833—1905), who, from 1857 onwards, had constructed various experimental forms of breechloader, and the rifle became the French service weapon in 1866.

It was two o'clock. The enemy's fire slackened; something was going on which the volunteers could not make out. All at once there was a sharp unfamiliar detonation, resembling the whirring sound of a machine. The French had come into action.the rifle that defeated the Garibaldians was so called after its inventor, Antoine Alphonse Chassepot (1833—1905), who, from 1857 onwards, had constructed various experimental forms of breechloader, and the rifle became the French service weapon in 1866.  In the following year it made its first appearance on the battlefield at Mentana on 3 November 1867, where it inflicted severe losses upon Giuseppe Garibaldi‘s troops. It was reported at the French Parliament that “Les Chassepots ont fait merveille!”, or loosely translated : “The Chassepots have done exceedingly well.

In the following year it made its first appearance on the battlefield at Mentana on 3 November 1867, where it inflicted severe losses upon Giuseppe Garibaldi‘s troops. It was reported at the French Parliament that “Les Chassepots ont fait merveille!”, or loosely translated : “The Chassepots have done exceedingly well. mentana

mentana A hailstorm of bullets mowed down the Garibaldian ranks. Their two guns were useless, for the ammunition, seventy rounds in all, was exhausted. They fought till four o'clock—till nearly their last cartridge was gone; then they slowly retreated. Very few of them guessed what that peculiar sound meant, or imagined that they had been engaged with the French, but next morning Europe knew from General De Failly's report that 'the Chassepots had done wonders.'

Garibaldi left the field, haggard and aged, unable to reconcile himself to a defeat which he thought that more discipline, more steadiness in his rank and file, would have turned into a victory. He had always demanded the impossible of his men; till now they had given it to him. In time he judged more justly. Those miserably-armed lads who lately had been glad to eat the herbs of the field, if haply they found any, stood out for four hours against the pick of two regular armies, one of which was supposed to be the finest in the world. They had done well.

Mentana remained that night in the hands of 1500 Garibaldians, who still occupied the castle and most of the houses when the general retreat was ordered. In the morning the Garibaldian officer who held the castle capitulated, on condition that the volunteers 'shut up in Mentana' should be reconducted across the frontier; terms which the French and Papal generals interpreted to embrace only the defenders of the castle. Eight hundred of the others were taken in triumph to Rome. It would have been wiser to let them go. The Romans had been told that the Garibaldians were cut-throats, incendiaries, human bloodhounds waiting to fly at them.

What did they behold? 'The beast is gentle,' as Euripides makes his captors say of Dionysius. The stalwart Romans saw a host of boys, with pale, wistful, very young-looking faces. If anything was wanting to seal the fate of the Temporal Power it was the sight of that procession of famished and wounded Italians brought to Rome by the foreigner.

What did they behold? 'The beast is gentle,' as Euripides makes his captors say of Dionysius. The stalwart Romans saw a host of boys, with pale, wistful, very young-looking faces. If anything was wanting to seal the fate of the Temporal Power it was the sight of that procession of famished and wounded Italians brought to Rome by the foreigner.

The victors, however, were jubilant. Their inharmonious shouts of Vive Pie Neuf vexed the delicate Roman ears. It was the battle-cry of the day of Mentana. Begun by the masked, finished by the unmasked soldiers of France, Mentana was a French victory, and it was the last.

The Garibaldian retreat continued through the night to Passo Corese (above) on the Italian frontier. The silence of the Campagna was only broken by little gusts of a chilly wind off the Tiber; it seemed as if a spectral army moved without sound.

Garibaldi rode with his hat pressed down over his eyes; only once he spoke: 'It is the first time they make me turn my back like this,' he said to an old comrade, 'it would have been better ...' He stopped, but it was easy to supply the words: 'to die.'

Garibaldi rode with his hat pressed down over his eyes; only once he spoke: 'It is the first time they make me turn my back like this,' he said to an old comrade, 'it would have been better ...' He stopped, but it was easy to supply the words: 'to die.'

As he was getting into the train at Figline, with the intention of going straight to Caprera, he was placed under arrest by order of the Italian Government. His officers had their hands on their swords, but he forbade their using force. The arrest seemed an unnecessary slight on the beaten man, who had loved Italy too well. But General Menabrea, who ordered it, believes that he thereby saved Italian unity. According to an account given by him many years after to the correspondent of an English newspaper, Napoleon wrote at this juncture to King Victor Emmanuel, that as he was not strong enough to govern his kingdom, he, Napoleon, was about to help him by relieving him of all parts of it except Piedmont, Lombardy and Venetia. The arrest of Garibaldi, by showing that the King 'could govern,' averted the impending danger. In communicating it to Napoleon, the King is said to have added 'that Italians would lose their last drop of blood before consenting to disruption,' a warning which he was not unlikely to give, but the whole story lacks verisimilitude. It appears more credible that an old man's memory is at fault than that a letter, so colossally insolent, was actually written. Menabrea, and even the King, may have feared that something of the kind was in the mind of the Emperor.

As after Aspromonte so after Mentana; Garibaldi was confined in the fortress of Varignano, on the bay of Spezia. A few weeks later he was released and sent to Caprera. As he left the fortress-prison he wrote the words: 'Farewell, Rome; farewell, Capitol; who knows who will think of thee, and when?'

The last crusade was over; destiny would do the rest

Bravo!

ReplyDeletegrazie

ReplyDelete