characters. Rattazzi held ministerial office under him, and the long Tuscan crisis of 1859, looked at, as he looked at it, from the inside, gave him opportunities of judging the Iron Baron who opposed even his own will on more than one occasion in that great emergency. Ricasoli was rigid, frigid, a frequenter of the straightest possible roads; Rattazzi, supple, accommodating, with an incorrigible partiality for umbrageous by-ways. He was already an 'old parliamentary hand,' and in the future, through a series of ministerial lapses, any one of which would have condemned most men to seclusion, he preserved his talent for manufacturing majorities and holding his party together. Choosing between these two candidates, Cavour before he died gave his preference to Ricasoli, who was charged by the King with the formation of a ministry in which he took the Treasury and the Foreign Office.

characters. Rattazzi held ministerial office under him, and the long Tuscan crisis of 1859, looked at, as he looked at it, from the inside, gave him opportunities of judging the Iron Baron who opposed even his own will on more than one occasion in that great emergency. Ricasoli was rigid, frigid, a frequenter of the straightest possible roads; Rattazzi, supple, accommodating, with an incorrigible partiality for umbrageous by-ways. He was already an 'old parliamentary hand,' and in the future, through a series of ministerial lapses, any one of which would have condemned most men to seclusion, he preserved his talent for manufacturing majorities and holding his party together. Choosing between these two candidates, Cavour before he died gave his preference to Ricasoli, who was charged by the King with the formation of a ministry in which he took the Treasury and the Foreign Office.

Ricasoli was without ambition, and he rather under than over-rated his abilities, but he went to work with considerable confidence in his power of setting everything right. A perfectly open and honest statesman ought to be able, he imagined, to solve the most difficult problems. Why not, except that the world is not what it ought to be? In home politics he offended the Party of Action by telling them plainly that if they broke the law they would have to pay the cost, and he offended his own party by refusing to interfere with the right of meeting or any other constitutional right of citizens, whether they were followers of Mazzini or of anybody else, as long as they kept within legal bounds.

He wrote an elaborate letter to Pius IX., in which he sought to persuade the Pontiff of the sweet reasonableness of renouncing claims which, for a very long spell, had cast nothing but discredit on religion. Ricasoli's attitude towards the Temporal Power was unique in this century. Like Dante's, his hatred of it was religious. He was a Catholic, not because he had never thought or studied, but because, having thought and studied, he assented, and from this standpoint he ascribed most of the wounds of the Church to her subordination of her spiritual mission to material interests.

He encouraged Padre Passaglia to collect the signatures of priests for a petition praying the Pope to cease opposing the desires of all Italy; 8943 names were affixed in a short time. The only result of these transactions was that Cardinal Antonelli remarked to the French Government that the Holy See would never come to terms with robbers, and that, although at war with the Turin Cabinet, 'the Pope's relations with Italy were excellent.' More harmful to Ricasoli than the fulminations of the Vatican was the veiled but determined hostility of Napoleon III. Cavour succeeded in more or less keeping the Emperor in ignorance of the degree to which their long partnership resembled a duel. He made him think that he was leading while he was being led. With Ricasoli there could be no such illusions. Napoleon understood him to be a man whom he might break, not bend. He thought it desirable to break him, and Imperial desires had many channels, at that time, towards fulfilment.

The Parting

The PartingThe Ricasoli ministry fell in February 1862, and, as a matter of course, Rattazzi was called to power. The new premier soon ingratiated himself with the King, who found him easier to get on with than the Florentine grand seigneur; with Garibaldi, whom he persuaded that some great step in the national redemption was on the eve of accomplishment; with Napoleon, who divined in him an instrument. Meanwhile, in his own mind, he proposed to eclipse Cavour, out-manoeuvre all parties, and make his name immortal. This remains the most probable, as it is the most lenient interpretation to which his strange policy is open.

Garibaldi was encouraged to visit the principal towns of North Italy in order to institute the Tiro Nazionale or Rifle Association, which was said to be meant to form the basis of a permanent volunteer force on the English pattern. For many reasons, such a scheme was not likely to succeed in Italy, but most people supposed the object to be different—namely, the preparation of the youth of the nation for an immediate war. The idea was strengthened when it was observed that Trescorre(above the villa terzi in Trescorre), in the province of Bergamo, where Garibaldi stopped to take a course of sulphur baths, became the centre of a gathering which included the greater part of his old Sicilian staff. There was no concealment in what was done, and the Government manifested no alarm.

The air was full of rumours, and in particular much was said about a Garibaldian expedition to Greece, for which, it was stated and re-stated, Rattazzi had promised £40,000. That Garibaldi meant to cast his lot in any struggle not bearing directly on Italian affairs, as long as the questions of Rome and Venice still hung in the balance, is not to be believed. A little earlier than this date, President Lincoln invited him to take the supreme command of the Federal army in the war for the Union, and he declined the offer, attractive though it must have been to him, both as a soldier and an abhorrer of slavery, because he did not think that Italy could spare him.

trescore

trescoreBut the 'Greek Expedition,' though a misleading name, was not altogether a blind. Before Cavour's death, there had been frequent discussion of a project for revolutionising the east of Europe on a grand scale; Hungary and the southern provinces of the Austrian Empire were to co-operate with the Slavs and other populations under Turkey in a movement which, even if only partially successful, would go far to facilitate the liberation of Venice. It cannot be doubted that Rattazzi's brain was at work on something of this sort, but the mobilisation, so to speak, of the Garibaldians suggested proceedings nearer home. Trescorre was very far from the sea, very near the Austrian frontier.

sarnico

sarnicoIn spite of contradictions, a plan for invading the Trentino, or South Tyrol, almost certainly did exist. Whether Garibaldi was alone answerable for it cannot be determined. The Government became suddenly alive to the enormous peril such an attack would involve, and arrested several of the Garibaldian officers at Sarnico. They were conveyed to Brescia, where a popular attempt was made to liberate them; the troops fired on the crowd, and some blood was shed. Garibaldi wrote an indignant protest and retired, first to the villa of Signora Cairoli at Belgirate(below), and then to Caprera. He did not, however, remain there long.

After this point, the thread of events becomes tangled beyond the hope of unravelment. What were the causes which led Garibaldi into the desperate venture that ended at Aspromonte?

Recollecting his hesitation before assuming the leadership of the Sicilian expedition, it seemed the more unintelligible that he should now undertake an enterprise which, unless he could rely on the complicity of Government, had not a single possibility of success.

His own old comrades were opposed to it, and it was notorious that Mazzini, to whom the counsels of despair were generally either rightly or wrongly attributed, had nothing to do with inspiring this attempt. In justice to Rattazzi, it must be allowed that, after the arrests at Sarnico, Garibaldi went into open opposition to the ministry, which he denounced as subservient to Napoleon. Nevertheless, with the remembrance of past circumstances in his mind, he may have felt convinced that the Prime Minister did not mean or that he would not dare to oppose him by force. One thing is certain; from beginning to end he never contemplated civil war. His disobedience to the King of Italy had only one purpose—to give him Rome. He was no more a rebel to Victor Emmanuel than when he marched through Sicily in 1860.

criel models usa

criel models usa The earlier stages of the affair were not calculated to weaken a belief in the effective non-intervention of Government. Garibaldi went to Palermo, where he arrived in the evening of the 28th of June. The young Princes Umberto and Amedeo were on a visit to the Prefect, the Marquis Pallavicini, and happened to be that night at the opera. All at once they perceived the spectators leave the house in a body, and they were left alone; on asking the reason, they heard that Garibaldi had just landed—all were gone to greet him! Before the departure of the Princes next day, the chief and his future King had an affectionate meeting, while the population renewed the scenes of wild enthusiasm of two years ago. Some of Garibaldi's intimate friends assert that when he reached Palermo he had still no intention of taking up arms. He soon began, however, to speak in a warlike tone, and at a review of the National Guard in presence of the Prefect, the Syndic, and all the authorities, he told the 'People of the Vespers' that if another Vespers were wanted to do it, Napoleon III., head of the brigands, must be ejected from Rome. The epithet was not bestowed at random; Lord Palmerston confirmed it when he said from his place in the House of Commons: 'In Rome there is a French garrison; under its shelter there exists a committee of 200, whose practice is to organise a band of murderers, the scum and dross of every nation, and send them into the Neapolitan territory to commit every atrocity!' As a criticism the words are not less strong; but the public defiance of Napoleon, and the threat with which it was accompanied, dictated one plain duty to the Italian Government if they meant to keep the peace—the arrest of Garibaldi and his embarkation for Caprera.

This they did not do; confining themselves to the recall of the Marquis Pallavicini. Garibaldi went over the ground made glorious by his former exploits—past Calatafimi to Marsala. It was at Marsala that, while he harangued his followers in a church, a voice in the crowd raised a cry of 'Rome or death!' 'Yes; Rome or death!' repeated Garibaldi; and thus the watchword originated which will endure written in blood on the Bitter Mount and on the Plain of Nomentum. Who raised it first? Perhaps some humble Sicilian fisherman. Its haunting music coming he knew not whence, sounding in his ear like an omen, was what wedded Garibaldi irrevocably to the undertaking. It was the casting interposition of chance, or, shall it be said, of Providence? Like all men of his mould, Garibaldi was governed by poetry, by romance. Besides the general patriotic sentiment, he had a peculiar personal feeling about Rome, 'which for me,' he once wrote, 'is Italy.' In 1849, the Assembly in its last moments invested him with plenary powers for the defence of the Eternal City, and this vote, never revoked, imposed on his imagination a permanent mandate. 'Rome or death' suggested an idea to him which he had never before entertained, prodigal though he had been of his person in a hundred fights: What if his own death were the one thing needful to precipitate the solution of the problem? francavilla in the salento. It was a typical town of the period where many were for Naples but many against. The nineteenth century for this town was a path from the fermented Risorgimento era and by bloody clashes, with Naples exterminating various seven carbonare groups.. After the unification of Italy, the development of the city was also facilitated by the construction of the railroad Taranto-Brindisi. in 1864 it assumed the current name of francavilla Fontana, from the Byzantine icon depicting the Madonna of the fountain and to remember the episode of its founder.

francavilla in the salento. It was a typical town of the period where many were for Naples but many against. The nineteenth century for this town was a path from the fermented Risorgimento era and by bloody clashes, with Naples exterminating various seven carbonare groups.. After the unification of Italy, the development of the city was also facilitated by the construction of the railroad Taranto-Brindisi. in 1864 it assumed the current name of francavilla Fontana, from the Byzantine icon depicting the Madonna of the fountain and to remember the episode of its founder.

francavilla in the salento. It was a typical town of the period where many were for Naples but many against. The nineteenth century for this town was a path from the fermented Risorgimento era and by bloody clashes, with Naples exterminating various seven carbonare groups.. After the unification of Italy, the development of the city was also facilitated by the construction of the railroad Taranto-Brindisi. in 1864 it assumed the current name of francavilla Fontana, from the Byzantine icon depicting the Madonna of the fountain and to remember the episode of its founder.

francavilla in the salento. It was a typical town of the period where many were for Naples but many against. The nineteenth century for this town was a path from the fermented Risorgimento era and by bloody clashes, with Naples exterminating various seven carbonare groups.. After the unification of Italy, the development of the city was also facilitated by the construction of the railroad Taranto-Brindisi. in 1864 it assumed the current name of francavilla Fontana, from the Byzantine icon depicting the Madonna of the fountain and to remember the episode of its founder.From Marsala he returned to Palermo, where, in the broad light of day, he summoned the Faithful, who came, as usual, at his bidding, without asking why or where?—the happy few who followed him in 1859 and 1860; who would follow him in 1867, and even in 1870, when they gave their lives for a people that did not thank them, because he willed it so. He sent out also a call to the Sicilian Picciotti, the Squadre of last year; and it is much to their credit that they too who cared possibly remarkably little for Roma Capitale, obeyed the man who had freed them. And Rattazzi knew of all this, and did nothing.

royal palace in Ficuzza

royal palace in FicuzzaOn the 1st of August, Garibaldi took command of 3000 volunteers in the woods of Ficuzza. Then, indeed, the Government wasted much paper on proclamations, and closed the door of the stable when the horse was gone. General Cugia was sent to Palermo to repress the movement. Nevertheless Garibaldi, with his constantly increasing band, made a triumphant progress across the island, and a more than royal entry into Catania. At Mezzojuso he was present at a Te Deum chanted in his honour. On the 22nd, when the royal troops were, it seems, really ordered to march on Catania, Garibaldi took possession of a couple of merchant vessels that had just reached the port, and sailed away by night for the Calabrian coast with about 1000 of his men.Below Bersaglieri by atlantic 60mm in plastic

By this time the Italian Government, whether by spontaneous conviction or by pressure from without, had resolved that the band should never get as far as the Papal frontier. If Garibaldi knew or realised their resolution, it is a mystery why he did not attempt to effect a landing nearer that frontier, if not actually within it. The deserted shore of the Pontine marshes would, one would think, have offered attractions to men who were as little afraid of fever as of bullets. A sort of superstition may have ruled the choice of the path, which was that which led to victory in 1860. It was not practicable, however, to follow it exactly. The tactics were different. Then the desire was to meet the enemy anywhere and everywhere; now the pursuer had to be eluded, because Garibaldi was determined not to fight him. Thus, instead of marching straight on Reggio, the volunteers sought concealment in the great mountain mass which forms the southernmost bulwark of the Apennines. The dense and trackless forests could have given cover for a long while to a native brigand troop, with intimate knowledge of the country and ways and means of obtaining provisions—not to a band like this of Garibaldi. They wandered about for three days, suffering from almost total want of food, and from the great fatigue of climbing the dried-up watercourses which serve as paths. On the 28th of August they reached the heights of Aspromonte—a strong position, from which only a large force could have dislodged them had they defended it.

Pallavicini started with six or seven battalions of Bersaglieri. It was the 29th of August. Garibaldi saw them coming when they were still three miles off. He could have dispersed his men in the forest and himself escaped, for the time, and perhaps altogether, for the sea which had so often befriended him was not far off. But although he did not mean to resist, a dogged instinct drove away the thought of flight. In the official account it was stated that an officer was sent in advance of the royal troops to demand surrender. No such officer was seen in the Garibaldian encampment till after the attack. The troops rapidly ascended an eminence, facing that on which the Garibaldians were posted, and opened a violent fusillade, which, to Garibaldi's dismay, was returned for a few minutes by his right, consisting of young Sicilians who were not sufficiently disciplined to stand being made targets of without replying. The contention, however, that they were the first to fire, has the testimony of every eye-witness on the side of the volunteers against it.

Pallavicini started with six or seven battalions of Bersaglieri. It was the 29th of August. Garibaldi saw them coming when they were still three miles off. He could have dispersed his men in the forest and himself escaped, for the time, and perhaps altogether, for the sea which had so often befriended him was not far off. But although he did not mean to resist, a dogged instinct drove away the thought of flight. In the official account it was stated that an officer was sent in advance of the royal troops to demand surrender. No such officer was seen in the Garibaldian encampment till after the attack. The troops rapidly ascended an eminence, facing that on which the Garibaldians were posted, and opened a violent fusillade, which, to Garibaldi's dismay, was returned for a few minutes by his right, consisting of young Sicilians who were not sufficiently disciplined to stand being made targets of without replying. The contention, however, that they were the first to fire, has the testimony of every eye-witness on the side of the volunteers against it.

pallavicini later fought against partizans and the outlaws note the hats

All the Garibaldian bugles sounded 'Cease firing,' and Garibaldi walked down in front of the ranks conjuring the men to obey. While he was thus employed, a spent ball struck his thigh, and a bullet entered his right foot. At first he remained standing, and repeated, 'Do not fire,' but he was obliged to sit down, and some of his officers carried him under a tree. The whole 'feat of arms,' as General Cialdini described it, did not last more than a quarter of an hour.

54mm piece for diorama

54mm piece for dioramaPallavicini approached the wounded hero bareheaded, and said that he made his acquaintance on the most unfortunate day of his own life. He was received with nothing but kind praise for doing his duty. The first night was passed by the prisoner in a shepherd's hut. The few devoted followers who were with him were strangely impressed by that midnight watch; the moon shining on the forest, the shepherds' dogs howling in the mountain silence, and their chief lying wounded, it might be to death, in the name of the King to whom he had given this land.

Next day, in a litter sheltered from the sun with branches of wild laurel, Garibaldi was carried down the steep rocks to Scilla, whence he was conveyed by sea to the fort of

It was not till after months of acute suffering, borne with a gentleness that made the doctors say: 'This man is not a soldier, but a saint,' that, through the skill of the French surgeon, Nélaton(below), the position of the ball was determined, and its extraction rendered possible.

A general amnesty issued on the occasion of the marriage of the King's second daughter with the King of Portugal relieved the Government of having to decide whether Garibaldi was to be tried, and if so, what for; but the unpopularity into which the ministry had fallen could not be so easily dissipated. The Minister of Foreign Affairs (Durando) published a note in which it was stated that Garibaldi had only attempted to realise, in an irregular way, the desire of the whole nation, and that, although he had been checked, the tension of the situation was such that it could not be indefinitely prolonged. This was true, but it hardly improved the case for the Government. In Latin countries, ministers do not cling to power; as soon as the wind blows against them, they resign to give the public time to forget their faults, and to become dissatisfied with their political rivals. Usually a very short time is required. Therefore, forestalling a vote of censure in the Chambers, where he had never yet had a real majority, Rattazzi resigned office with a parting homily in which he claimed to have saved the national institutions.

The administration which followed contained the well-known names of Farini, Minghetti, Pasolini, Peruzzi, Delia Rovere, Menabrea. When Farini's fatal illness set in, Minghetti replaced him as Prime Minister, and Visconti Venosta took the Foreign Office. They found the country in a lamentable state, embittered by Aspromonte, still infected with brigandage, and suffering from an increasing deficit, coupled with a diminishing revenue. The administrative and financial unification of Italy, still far from complete, presented the gravest difficulties. The political aspect of affairs, and especially the presence of the French in Rome, provoked a general sense of instability which was contrary to the organisation of the new state and the development of its resources. The ministers sought remedies or palliatives for these several evils, and to meet the last they opened negotiations with France, which resulted in the compromise known as the September Convention.

It was long before the treaty was concluded, as for more than a year the French Government refused to remove the garrison on any terms; but in the autumn of 1864 the following arrangement was signed by both parties: that Italy should protect the Papal frontier from all attack from the outside; that France should gradually withdraw her troops, the complete evacuation to take place within two years; that Italy should waive the right of protest against the internal organisation of the Papal army unless its proportions became such as to be a manifest threat to the Italian kingdom; that the Italian capital should be moved to Florence within six months of the approval of the Convention by Parliament.

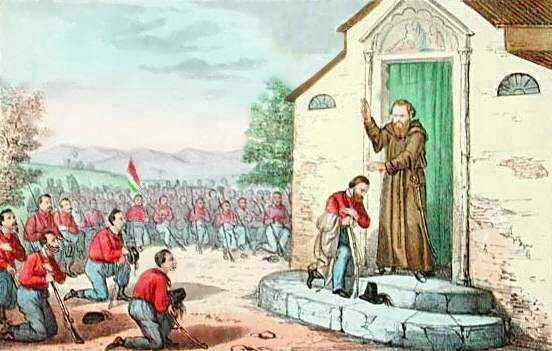

It was long before the treaty was concluded, as for more than a year the French Government refused to remove the garrison on any terms; but in the autumn of 1864 the following arrangement was signed by both parties: that Italy should protect the Papal frontier from all attack from the outside; that France should gradually withdraw her troops, the complete evacuation to take place within two years; that Italy should waive the right of protest against the internal organisation of the Papal army unless its proportions became such as to be a manifest threat to the Italian kingdom; that the Italian capital should be moved to Florence within six months of the approval of the Convention by Parliament. Fra Giovanni Pantaleo was born in Castelvetrano 1832. Franciscan Friar of the order, and then studied in Salemi in Palermo. He was Professor of moral philosophy in the archiepiscopal seminar, but soon his superiors took the Chair because his philosophy was considered contrary to the dogmas of the Church. In 1859 he participated in moti organized by father Lanza to do arise Palermo against the Bourbons. Upon arrival of a thousand in Sicily, he joined Garibaldi tracking him in all his battles in Italy and out. Abandoned the robe was married in Lyon with Camilla Vahè on 22 June 1872 matrimony sparked numerous controversies is among his supporters that between political opponents. He fought from citizen and soldier on Aspramonte in 1862, in the Tyrol in 1866, at Mentana in 1867 and finally in France in Dijon with the rank of major. He lived in Rome with the old mother, sister and family which had been created. He was humble trades, without anything ask itself but by encouraging hundreds. He died poor in Rome on 3 August 1879 leaving the family in the most squalid poverty. Spoke all the newspapers of that time. For the occasion was created a Committee to help the family. The friar, during his adventurous existence, had had the opportunity to lead a good life, but, being an idealist, had refused any opportunity of having a future material prosperity for themselves and family. Joined Garibaldi in Naples, between Pantaleo, with his sister and his mother, he went to live in the Palace of the Prince of s.Antimo, off Mercatello, today piazza Dante. Became a symbol "public trust", receiving money and gifts offered by the citizens for the cause of Italy. Pantaleo, took advantage of a lira ever: all official receipt was issued. By Decree of 5 November 1860, Garibaldi appointed between Pantaleo, Vicar to Senior Chaplain of the Kingdom in the island of Sicily. The Friar refused that title that the privileges conferred, honours, own revenue and episcopal dignity, because he felt worthy of the high post. He accepted the appointment of Abbot of SS. Trinity of Castiglione and St. Philip the Great, that allowed him to his mother and sister to have an annual annuity of lire 347,72. The General knew the economic needs of the family of between Pantaleo. After his death, we were told that on January 7, 1862, in consideration of special merit purchased in the countryside of 1860, Vittorio Emanuele had awarded the honour of Knight of the order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. It brings back a letter written by Caprera Garibaldi for Pantaleo:

Fra Giovanni Pantaleo was born in Castelvetrano 1832. Franciscan Friar of the order, and then studied in Salemi in Palermo. He was Professor of moral philosophy in the archiepiscopal seminar, but soon his superiors took the Chair because his philosophy was considered contrary to the dogmas of the Church. In 1859 he participated in moti organized by father Lanza to do arise Palermo against the Bourbons. Upon arrival of a thousand in Sicily, he joined Garibaldi tracking him in all his battles in Italy and out. Abandoned the robe was married in Lyon with Camilla Vahè on 22 June 1872 matrimony sparked numerous controversies is among his supporters that between political opponents. He fought from citizen and soldier on Aspramonte in 1862, in the Tyrol in 1866, at Mentana in 1867 and finally in France in Dijon with the rank of major. He lived in Rome with the old mother, sister and family which had been created. He was humble trades, without anything ask itself but by encouraging hundreds. He died poor in Rome on 3 August 1879 leaving the family in the most squalid poverty. Spoke all the newspapers of that time. For the occasion was created a Committee to help the family. The friar, during his adventurous existence, had had the opportunity to lead a good life, but, being an idealist, had refused any opportunity of having a future material prosperity for themselves and family. Joined Garibaldi in Naples, between Pantaleo, with his sister and his mother, he went to live in the Palace of the Prince of s.Antimo, off Mercatello, today piazza Dante. Became a symbol "public trust", receiving money and gifts offered by the citizens for the cause of Italy. Pantaleo, took advantage of a lira ever: all official receipt was issued. By Decree of 5 November 1860, Garibaldi appointed between Pantaleo, Vicar to Senior Chaplain of the Kingdom in the island of Sicily. The Friar refused that title that the privileges conferred, honours, own revenue and episcopal dignity, because he felt worthy of the high post. He accepted the appointment of Abbot of SS. Trinity of Castiglione and St. Philip the Great, that allowed him to his mother and sister to have an annual annuity of lire 347,72. The General knew the economic needs of the family of between Pantaleo. After his death, we were told that on January 7, 1862, in consideration of special merit purchased in the countryside of 1860, Vittorio Emanuele had awarded the honour of Knight of the order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus. It brings back a letter written by Caprera Garibaldi for Pantaleo:These terms were in part the same as those proposed by Prince Napoleon to Cavour shortly before the death of that statesman, who had promised to support them as a temporary makeshift, and in order to get the French out of Italy. But they were in part different, and they contained two new provisions which it is morally certain that Cavour would never have agreed to—the prolongation of the French occupation for two years (Cavour had insisted that it should cease in a fortnight), and the transfer of the capital, which was now made a sine quâ non by Napoleon, for evident reasons. While it was clear that Turin could not be the permanent capital of a kingdom that stretched to Ætna, if once the seat of government were removed to Florence a thousand arguments and interests would spring up in favour of keeping it there. So, at least, it was sure to seem to a foreigner. As a matter of fact, the solution was no solution; the Italians could not be reconciled to the loss of Rome either by the beauty and historic splendour of the city on the Arno, or by its immunity from malaria, which was then feared as a serious drawback, though Rome has become, under its present rulers, the healthiest capital in Europe. But Napoleon thought that he was playing a trump card when he dictated the sacrifice of Turin.

The patriotic Turinese were unprepared for the blow. They had been told again and again that till the seat of government was established on the Tiber, it should abide under the shadow of the Alps—white guardian angels of Italy—in the custody of the hardy population which had shown itself so well worthy of the trust. The ministry foresaw the effect which the convention would have on the minds of the Turinese, and they resorted to the weak subterfuge of keeping its terms secret as long as they could. Rumours, however, leaked out, and these, as usual, exaggerated the evil. It was said that Rome was categorically abandoned. On the 20th of September crowds began to fill the streets, crying: 'Rome or Turin!' and on the two following days there were encounters between the populace and the military, in which the latter resorted to unnecessary and almost provocative violence. Amidst the chorus of censure aroused by these events, the Minghetti cabinet resigned, and General La Marmora, who, as a Piedmontese, was fitted to soothe the excited feelings of his fellow-citizens, was called upon to form a ministry.

The change of capital received the sanction of Parliament on the 19th of November. Outside Piedmont it was not unpopular; people felt that, after all, it rested with themselves to make Florence no final halting-place, but a step towards Rome. The Papal Government, which had been a stranger to the late negotiations, expressed a supreme ] indifference to the whole affair, even to the contemplated departure of the French troops, 'which concerned the Imperial Government, not the Pope,' said Cardinal Antonelli, 'since the occupation had been determined by French interests.' It cannot be asserted that the Pope ever assumed a gratitude which he did not feel towards the monarch who kept him on his throne for twenty years. capture

capture

capture

capture

No comments:

Post a Comment